|

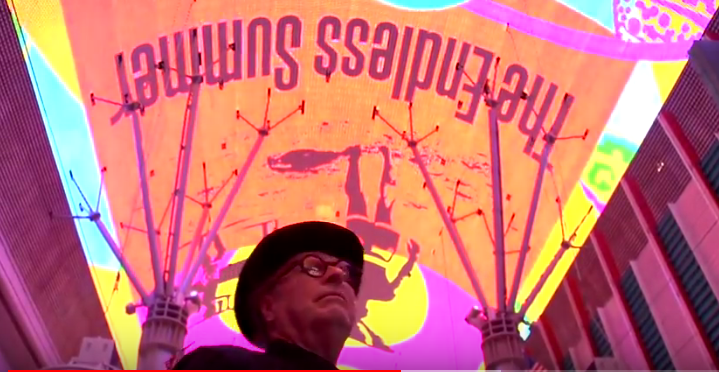

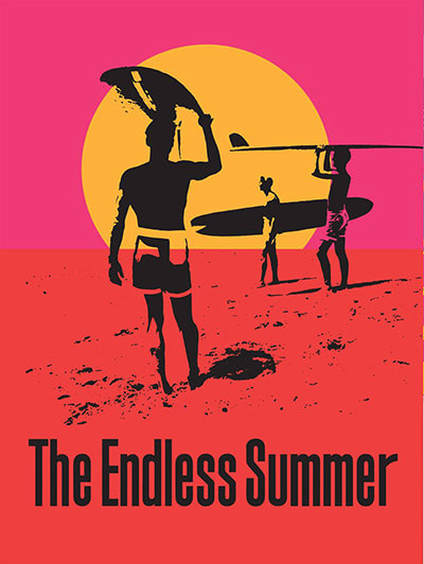

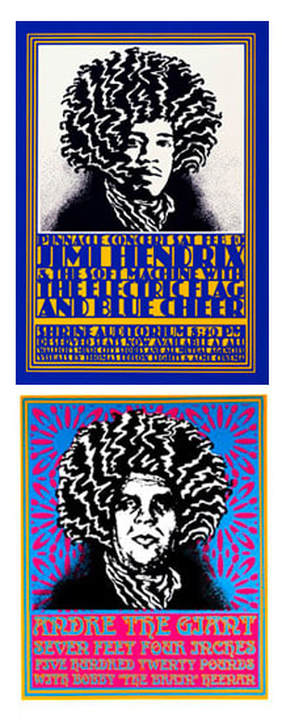

John Van Hamersveld's work in progress. Photo PaintThisDesert. Designer John van Hamersveld stood in front of his home that sits at an angle against the hills of Rancho Palos Verdes. With Sunday morning coolness he donned all black, topped off with a dapper hat. He wore his usual thick-framed glasses, custom made and named after him: The Hammer. They have the same boldness as the black lines seen in his illustrations. The black, the hat and the bold glasses are his costume, he says. John, or JVH as he is known, is the artist and designer with whom you’re likely already familiar. He’s created work since the 1960s and inspired many of today’s contemporary street artists. Walk in the house you see an archive of work that mark design history, and the books on the shelves and architecture of his home are a clue to his influences. He digs the modernists. Born in 1941, the child of the Sixties is a surfer-turned-Chouinard Art Institute student and best known for early landmark design that responded to cultural influences using modernist line and form. “Hard-edges...” says JVH softly, referring to the lines in the illustrations that were framed and sitting in his living room, that doubles as a studio. The prints were ready to picked up for “The Mural Show Loma” at Keller Art Gallery on the campus of Point Loma Nazarene University. It's an exhibition that is a cross history of his new and old works, and being curated to be read and “posed in a different way,” says JVH. It is also a way to show how a designer from the traditional printing era is elegantly basking in a digital world. Screen grab from a video featuring "Signs of Life" ( 2010) created by John Van Hamersveld for the Viva Vision at Las Vegas Fremont Street I YouTube Whole JVH was commissioned a mural for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, in many ways his return to public art was kicked off in 2009 and 2010. with "Signs of Life,” the Viva Vision Light Show for the Fremont Experience in downtown Las Vegas. It featured JVH’s signs and symbolism as a moving collage of image and color backed up with a 1960s rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack. The JVH public art portfolio grew from there and included the Hermosa Beach Mural Project (2015), Downtown Los Angeles 7th & Fig installation (2017), and The Vans Mural (2018) at their corporate facility. Even in static form the images are still a movement of layers in psychedelic colors that overlap and collide. These recent murals are evidence that he is still a bad boy of revamped Bauhaus with this public art that looks like it was created after he was partying with artist Ellsworth Kelly, designer Saul Bass, and theorist Marshall McLuhan in a hotel room, and tossed a television out the window as a rejected symbolism of media as message. While JVH has adjusted to many changes throughout his career, he notes that foundation began when studying under the mid-century New York school of artists who fled to the Coast. He also saw how design was aimed for consumers to attract “Service Style Dollars” that purchased lifestyle. Then it all changed again, and he kept up. “I wanted to go over the success of two decades over art and design, plus media,” he says of the upcoming show. It is as simple as revisiting his drawing ability and design vernacular that is applied and supported with digital technology. “I wanted the exhibit to go beyond his legacy of beach culture and 'The Endless Summer,'" says exhibition curator David Carlson. “It is valuable for students studying art and design to connect with the process of an artist.” The style that serves his public art made a debut as a poster: “The Endless Summer.” The graphic is still his calling card. It was designed in 1964 as key art for friend Bruce Brown, a surf culture documentarian. You know the image with the film’s two surfing subjects, Mike Hynson and Robert August, as shot by JVH at Salt Creek Beach in Dana Point. He took his photo and revisited it, the images were then screen-printed and titles hand lettered. Now in any exhibition or story on JVH, this poster with shadowed surfers on day-glo colors is always featured. It has been referred to as the California version of pop-art, or a cinematic throwback, but that is really the subtext. The artist gave us an image of a surfer’s crucible in waiting for a right wave. After the poster for “The Endless Summer” was introduced it become part of surfing lore. JVH then went on to work at Capitol Records to design album covers, including the Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour” and The Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main St.” His is also known for the now-classic Jimi Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane Pinnacle Rock Concert posters, a look that was anti-establishment by way of corporate budgets. Jimi Hendrix was given an iconic look that was a reference to the idea that he was already recognized as an experimental rock God, a classical musician of his era. In turn, for New West Symphony, JVH turned Ludwig Van Beethoven into a long-haired rock star, a classical musician become whose locks became bolts of electricity. For five decades John van Hamersveld has been using his mastery of hard lines for an organic connection to image and message, spiked with Surfer-Hippie cultural politics. He guided design to brand pop-culture identity to an international audience, all with a California attitude that stands at the front door greeting those who want to share the vibe.

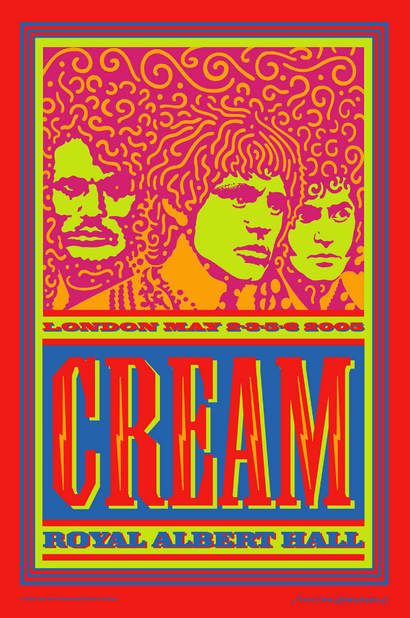

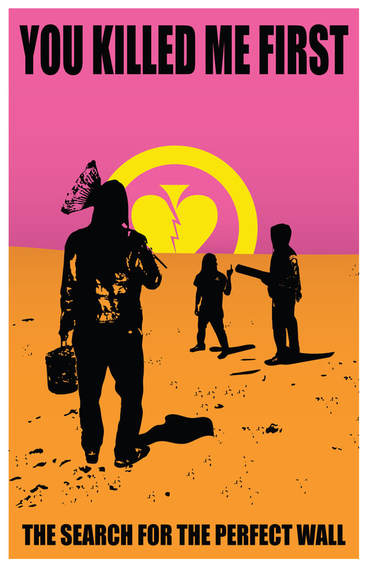

"The Endless Summer" documentary and poster reached its 50th anniversary in 2014. The film had a limited release in 1964 before being released worldwide in 1966. Courtesy John van Hamersveld JHV's 2005 poster for Cream. Courtesy John van Hamersveld. John Van Hamersveld "Water Tank Mural" (2018) El Segundo, California. Courtesy the artist. JVH influence on Shepard Fairey's early thinking about design as art began with this poster promoting Jimi Hendrix. “I think that image immediately made an impression on me...the significance of it a perfect icon really sunk in," Fairey said in a conversation with JVH. "There is no more (visual) information than necessary." JVH influence is counted in decades. Las Vegas-based street artist YKMF paid homage to JVH in a recent reappropriation of "The Endless Summer." Courtesy of the artist. John van Hamersveld at home, in the summer of 2018. Photo PaintThisDesert

0 Comments

College of Southern Nevada Fine Arts Gallery host visiting artist Shona Macdonald. FIELD NOTES: Shona Macdonald “Overcast” at College of Southern Nevada Fine Arts Gallery opened July 13. From her paintings you will be taking a walk with her and see shallow water found along a path. Sometimes you will see a calm stillness briefly interrupted by the touch of a breeze.

Macdonald’s “Sky on Ground” series of small works and larger pieces are source by images she captured on walks with her camera. Her puddles on the earth are a painted representation that guide you to seeing uneventful objects in the reflection, an upside-down realism of a landscape detail that exists just beyond the canvas. In some you see powerlines from light poles made with brisk wavy delicate lines, a capture of motion caused by a breeze that taps the surface of water; movement in the still-life of still water. As intended by the artist, the works are prompted by romantic landscape painters like Caspar David Friedrich, who used painting to connect a spiritual read of the natural world. In some of Macdonald’s work you see leaves laying near leftover water, a spot of fall color framed by muted blue and greys, or earthy texture of dirt road graded for travel. If these works are prompted by traditions of European landscape paintings, the leaves, in all their realism, also has you think of art historian Paul Johnson’s reference to Aelbert Cuyp’s use of cattle in works like “A Herdsman with Five Cows by a River.” Cuyp’s bovine show calmness near a body of water and adds atmosphere. Macdonald’s leaves that fell from an unseen tree do the same in her work. And her use of image next to, or in a body of water to set a mood shifts away from provoking a sense of awe with distant observation. She uses details of a presumed landscape to magnify intimacy with a feeling of displacement. “Sky on Ground” is a pervasive series of contemporary paintings that are pensive observation that make a transition onto canvas to share a mood in all the works that uses melancholy as a subject. That gives weighted meaning to the title “Overcast.” Shona Macdonald will speak at the College of Southern Nevada Fine Arts Gallery on Thursday, September 6, at 4 p.m. “Overcast” closes September 8. Installation view of Vincent Valdez: The City at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, 2018. Purchase through the generosity of Guillermo C. Nicolas and James C. Foster in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, with additional support from Jeanne and Michael Klein and Ellen Susman in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2017. © Vincent Valdez Revisiting Vincent Valdez’s The City: Critical Moments of Silence and Reflection in Times of Distortion and Chaos By ANDREA LEPAGE Vincent Valdez’s “The City” has received a wide array of media coverage since its opening at the Blanton Museum of Art on July 17, 2018. In October 2016, I wrote a piece for PaintThisDesert when "The City" was on view at the David Shelton Gallery in Houston, Texas. Since then, the Blanton Museum of Art (UT Austin) purchased Valdez’s 30-foot-long painting depicting fourteen members of the Ku Klux Klan who stand in as allegorical representations of a longstanding and prevailing system of white supremacy in the United States. The hooded baby—cradled in a mother’s arms—leaves the viewer with the uncomfortable reminder that hate is transmitted seamlessly from one generation to the next. The intimidating hooded figures loom larger-than-life over the viewer and nearly obscure the distant gleaming city from which the composition takes its name. I pointed out in an essay written for the Blanton Museum’s gallery guide that Valdez’s painting calls for a visual comparison between overt and easily recognizable forms of racism (the Klan) and more covert and hidden forms (the city plan). Valdez’s inscription, “For PG & GSH,” located in the lower right corner acknowledges the prevalence of both manifestations. In paying homage to Philip Guston’s 1969 “City Limits” and Gil Scott-Heron’s 1980 visceral rendition of The Klan, Valdez inserts himself into a multi-generational artistic lineage alongside a painter and a musician who also opposed the Klan and their ideology. Vincent Valdez in his studio, 2016. © Michael Stravato “I hold very firm in my belief today that art and artists can still play a social role and that art can provide very crucial, critical moments of silence and reflection during moments of immense distortion and chaos.” - Vincent Valdez When the viewer confronts Valdez’s monumental painting, the eye first settles and lingers on the Klan members, infamous for their systematic and deadly targeting of mainly African American communities but also Latinos, Catholics, Jewish people, immigrants, and members of the LGBT community. Valdez discussed the disjunction between the beauty of their rendering and the horror of the Klan’s actions with journalist Maria Hinojosa of NPR’s “Latino USA” on the opening night at the Blanton Museum of Art. “Full blown raw reality is supposed to hit you. I lure you in with that beauty and I keep you there just enough so that you aren’t distracted within two seconds and back on your cell phone,” Valdez said. “If I can keep your attention, draw you in and keep you there, then that’s when the power of art really starts to unfold because you start to think critically.” Should attention shift to a cell phone, viewers will be met with a disconcerting reflection of themselves in the image of a Klansman who casually checks his phone. Close looking through the peaked hoods brings into high relief the significance of the gridded city in the background. Like the Klan members whose images encapsulate many forms of overt racism, the portrait of the city in the distance also assumes an allegorical role in the painting. City designs throughout the country play a key part in the systematic disenfranchisement of communities of color and immigrants. In discussing the point with Hinojosa, Valdez targeted a few of the many elements that are part of a whole system that disadvantages communities of color. County jails, high-density housing projects, and liquor stores are disproportionately placed in low income neighborhoods. Access to high-quality educational and health resources, on the other hand, are largely absent from the same communities. Underscoring the invisibility of some parts of the larger system of disenfranchisement, Valdez questioned, “Who gets trees and parks and playgrounds? Who gets access to these things?” His question conjures the image of the toddler whose pointing gesture seems to recruit the viewer to participate in a lifestyle that will ultimately support his ability to thrive. The Blanton Museum of Art also purchased the pendant piece, “The City II” (2016), which features a desolate dumping ground populated by abandoned mattresses, furniture, and television sets. “The City II” has received significantly less attention than its more jarring companion piece, yet, it is crucial in understanding a key theme that unites the multi-panel installation: American consumerism directly supports the maintenance of white supremacy. The iPhone, baby Nikes, special edition Budweiser beer can, and late model Chevrolet serve to locate the painting in the present. But these details set alongside the cast off possessions piled high in “The City II” also remind the viewer that the American drive to consume exacerbates and maintains vast racial and economic divides. “For far too long it’s been too easy for America to avoid the conversation about racism and how it is so embedded in our American DNA and our way of life,” Valdez said. Valdez began painting “The City” in 2015, during Barack Obama’s presidency. Now viewed in the context of the current administration, we might ask whether “The City” themes resonate more with today’s audience. By no means are individual or structural racism new to this nation. Nonetheless, discussions about white supremacy, structural racism, and xenophobia have reentered our conversations with alarming normalcy since the November 2016 election. If Valdez’s “The City” resonates more today in the midst of tweetstorms, inhumane immigrant child detainments, and continued killings of unarmed black men and women, it is because now, more than ever, we require critical moments of silence and reflection in times of political distortion and chaos. Vincent Valdez, The City I, 2015–16 (detail). Oil on canvas, 74 x 360 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of Guillermo C. Nicolas and James C. Foster in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, with additional support from Jeanne and Michael Klein and Ellen Susman in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2017. © Vincent Valdez. Photo by Peter Molick. Vincent Valdez’s “The City” can be seen at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin, through October 28, 2018. Andrea Lepage is associate professor of art history at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. As a scholar of Latino/a and Chicano/a visual culture coming out of the west, Lepage explores contemporary art as a form of social practice. Her many published writings include the essay “Reconstructing the Curriculum at El Taller Siqueiros, c. 1977: Judith Baca’s ‘Intensive Course in Mural Painting in Cuernavaca’ ” in “BACA: Art, Collaboration and Mural Making” (Angel City Press, 2017). |

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|