|

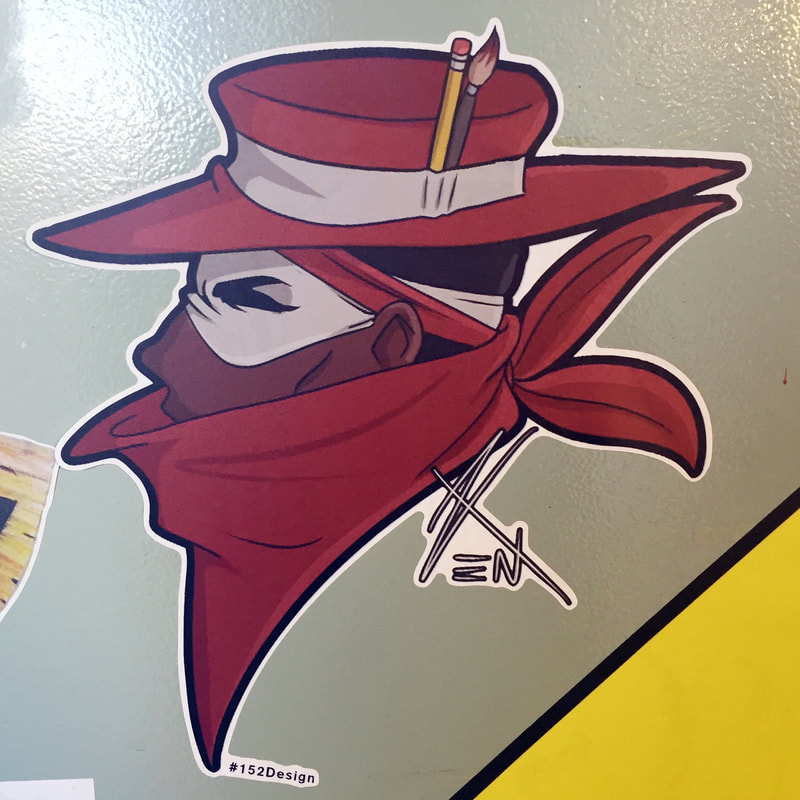

"(Left) Hear Us" Installation 2018 (Right) Poster by Christina Uran. Graphic Design is no longer be a vestige discipline at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. The College of Fine Arts has added design faculty and resources, and now it can keep up with a grounded photography program. Both design and photography can aim to match the gravitas of the painters and sculptors who graduated from the BFA and MFA programs. It also opens the door for 2D Design Fundamentals, a core class in any art program, to show how basics can be adjusted to an incoming wave of design students, and not just be a gateway to painting, drawing, and sculpture. And yea, I used the method of street art When I polled my 2D basic students on the first night of the fall semester, hands showed more than half were graphic design majors. That had me adjust the entry point in understanding the basics and consider the opening project use street art as the end execution. That aesthetic gives experienced and novice art students a shared starting point (other than comics and gaming). During the second class in the first week of the semester, ideas came out of a discussion on campus safety. In anticipation of events marking the first anniversary of October 1, students were asked if events from a year ago was still on their mind, and what was their point of view? The conversation was revealing. Because of that talk that became about campus safety, that provided content. An early assignment called “Visual Statement” was modified to respond to some of the topics brought up that night. The work made a debut, rather an infiltration, at the 2nd Annual Art Walk on October 12, days after a flurry of memorials were held. (UNLV is ten minutes away from the grounds where a gunman fired into the concert grounds). It also gave students the chance to create unsanctioned artwork executed outside of the context of traditional art venues. Though not in the street, the installation had foot traffic when people attending the art walk entered the courtyard. They were temporary works that can be pulled down easily, still a subsequent incarnation of stencil work, wheat-pastes and sticker art, the common forms of modern street art. They were installed on a door of the classroom numbered 152. Each piece uses the hashtag of #152Design. The classroom is across the way from an older guerrilla project; a large paper-mache ear, presumably representing Van Gogh’s lost appendage. The ear has been adopted by the art department and now a landmark piece. Building services even paints it the same color as Grant Hall when they spiffy up the building. It is also a mascot. Now the ear speaks. With the arrival of new chair Marcus Civin, it has been given its own Instagram account. While some of the names of the individual pieces were still waiting to be set by the artists, as a collective, near the ear, it became an installation titled “Hear Us.” The first directive was to make a statement on a caution sign. It strayed as artists played with the ideas of how design basics solve the problem of saying something with clarity to communicate a message. The usual practice of shading and perspective was traded out for coming up with an idea, play with balance, thinking of positive and negative space, forming a stronger sense of line and form to make it work; all to make an abstract idea clear. It also became a way to introduce students how to explain the work without the jumble of academia prose. When they pitched their ideas, they were instructed that was the beginning of an artist’s statement. They were to expand the pitch into a written assignment. Courtesy Megan Lufcy A few stayed with the original prompt of the image on a traffic warning sign; black graphic on a yellow background. “Two guns are pointed at each other, and one is a toy gun with an orange tip. Other than that, they look exactly the same,” wrote Megan Lufcy. “It's meant to get the viewer to think about the gun obsession in our country. We even give toy guns to children, and then wonder why they can't tell the difference when there's an accident with a real gun. I wasn't allowed to play with toy guns as a child, so that issue has always confused me.” Courtesy Patrick Manabat Some stayed with gun safety, but Patrick Manabat did not use the idea of a sign. “I originally wanted to emphasize the menacing look of the gun in contrast to the confetti which represents something more flamboyant; however, I felt that it could be interpreted in many different ways,” said Manabat. “I decided to leave that aspect as a part of the piece. This was just to get people thinking about the idea of gun safety, and to spark insight on the topic itself.” Others expanded beyond guns, but still stayed within the framework of “Visual Statement” as a personal comment. If there was another subject of safety they preferred to speak to, and their pitch was well thought out, it was accepted. Often the image became more personal. Daniel Darden had thoughts on prescription drugs. Courtesy Daniel Darden “Many people see prescription drugs as trustworthy since they are legal and come from a doctor, but there is a dark face behind what long term use and abuse of these drugs can do,” wrote Darden. “College students are always warned about drug use, but it seems that the message is off track and doesn’t stick a lot of the time. I believe this is because students are pushed to make their grades a priority over their mental health.” Courtesy Michelle Harper Michelle Harper used the assignment as the chance to question the school mascot, and deconstructed the meaning of Rebel. “With UNLV being an extremely diverse school, I thought the mascot should be as well. I reimagined the mascot as an indigenous man wearing a mask. I figured that with no specific race, many students could relate and identify with him more,” said Harper, whose hip vigilante “embraces the rebel culture we have at our school.” During the critique stage, the class was visited by Las Vegas-based street artists Sage Sage (There She Is Art) and Shawn Gatlin (You Killed Me First), whose wheat-pastes are seen primarily in the Las Vegas arts district and Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. The work from the class in room 152, thus the hashtag 152 design, follows cues from guerilla artists who create community relevant content that brings ephemeral attention to social causes through "art provocation." Courtesy Marlyne Lopez There were also opposing ideas. Marlyne Lopez preferred to be hopeful in a time of difficult questions. Her reasoning on the discussion was valid, and she was encouraged to approach the direction that was forming in her mind. In her statement she later wrote:

Lopez's art and statement was a gentle counterpoint to cautionary messages.

These undergrads not exhibited in galleries during art walk have them be like street artists isolated from the formal art world. By coming up with a concept, solution, then the application of basics to make an abstract idea clearer, they voiced ideas in public space, near the site of the October 1 shooting. That added meaning to the vulnerability and voice of students on an open campus.

0 Comments

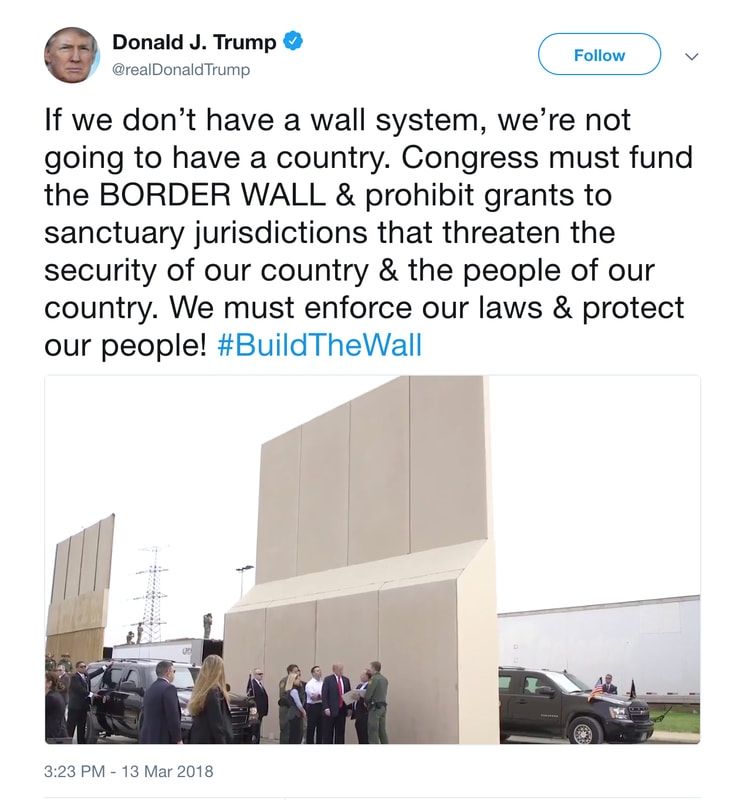

Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. By Andrea Lepage Mexican-born naturalized U.S. citizen, Xavier Tavera (b. 1971) recalls crossing the U.S.-Mexico border a few times with his family as a small child, saying, “I remember the tension and anxiety it produced when my family approached the crossing bridge by car.” Not breaking any laws, Tavera recollects that the family nonetheless waited in uneasy silence until they passed through the checkpoint. Tavera’s memory of crossing underscores the power of the border. The border has—since its inception—functioned as a visible manifestation of the U.S.'s perceived power and political dominance over its southern neighbor. In an interview, Tavera summarized the point: “Mexicans, Latinx and Chicanos—regardless of place of birth and migratory status, and even Latinx living in the U.S. that have never crossed the border—are deeply marked by the notion of border. ‘Border’ is a concept that has defined us symbolically and culturally.” President Donald Trump’s nativist rhetoric combined with his promises to enhance border security and build a border wall have led to increased international focus on the borderlands and those who pass through them. Tavera’s Borderlands series visually explores this territory and also considers the individuals who occupy it. He notes that his conceptualization of the Borderlands series emerged in response to the current administration’s language about the border, explaining, “The abrasive rhetoric that the current government administration has used towards the border has been one of the propelling motivations of this project.” The Borderlands photographs seek to mitigate the detrimental effects of such speech on Latinx communities by engineering close encounters with these individuals who occupy the region and by proposing imaginary alternatives to the border wall. Tavera took his first of three trips to the U.S.-Mexico border in January of 2017, intending to document the surrounding borderlands and to examine the border wall. Following its path, Tavera revisited the border in May of 2017 and again in March of 2018. He expects to return at least three more times to bring the Borderlands project to completion. During these trips, Tavera alters the photographed landscapes by digitally superimposing tables, tunnels, or shelters on the desolate terrain. In considering the possible use of these imaginary projects by unpictured communities, Tavera asked, “Would we find commonalities or differences in a given space? What would be the risks of communication and involvement with a different culture or community?” Tavera’s phrasing provides a counterpoint to Trump’s frequent anti-immigrant statements that emphasize difference and reject the possibility of cross-cultural commonality. Trump’s March 13, 2018 tweet—issued during Tavera’s third trip to the border—is representative of the U.S. president’s fear-inducing rhetoric: Tavera’s series visually rejects speech that casts the children and adults who cross the border with or without authorization as threats to U.S. citizens. Instead, the artist conceptualizes the border as a scar across the rugged landscape, a characterization that evokes Chicana theorist Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1987 description of the border in her seminal text Borderlands/La Frontera. Anzaldúa defined the border as both an injurious and injured site, “una herida abierta [an open wound] where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.” Extending Anzaldúa’s metaphor to the physical border barrier, Tavera concludes that "the political character of this open wound materializes in a wall with sentiments of nationalism, protectionism and absurdity.” Like Robert Misrach’s Border Cantos photographs, many of Tavera’s Borderlands images are unpopulated, revealing only the residues of human presence, and even those traces appear unwelcome. One of Tavera’s photographs centers on a set of chained tires of the kind that would be dragged behind U.S. border patrol trucks to smooth out the terrain. The procedure, variously called “pulling the drag,” “sign cutting,” or “cutting for sign,” allows border patrol agents to identify new footprints to track and capture migrants. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. Tavera’s photographs are part of an upsurge of border-related artwork produced since 2006, the year when then-president George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act. The bill sought to restrict passage across the border using systematic human and drone surveillance and through the creation of reinforced fencing. In one of his photographs, Tavera captures a surveillance blimp apparently preparing for flight under the cover of night. The star-like lights surrounding the blimp penetrate the pitch black landscape, serving as absurd beacons of protectionism amidst the expanse of the borderlands. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera.

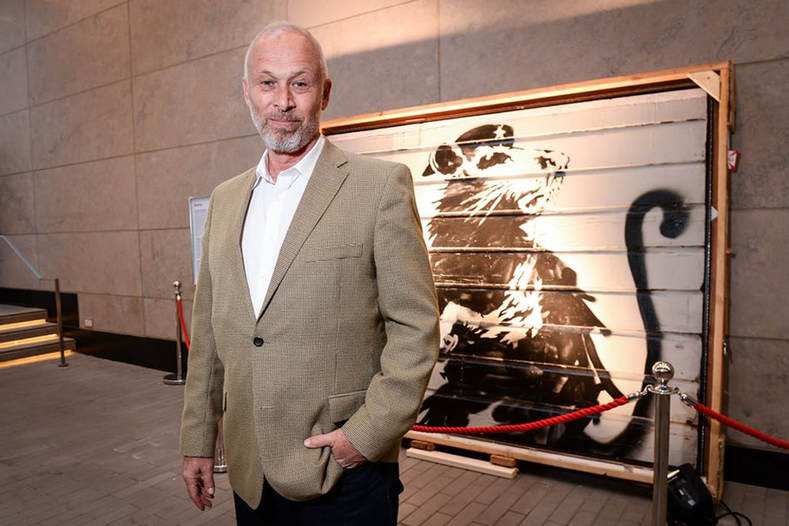

Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. "What I like about portraiture," Tavera said, "is the contact with the people.” In a 2016 interview, Tavera discussed the power of the camera to grant him access to people and to open a metaphorical window into their lives. He underscores that “the main purpose of this is to try to understand, not to make assumptions” about the sitters. Despite Trump’s attempt to conjure up the false image of an army of Mexicans ready to overtake the border, the U.S. is not a coveted destination for all. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. Tavera photographed three dancers on the streets of Nogales, Mexico, for example, who had no intention of crossing the border. Like Tavera, it was, instead, their destination. The dancers carried drums and each wore rattles crafted from empty bullet shells. In the course of their brief exchange, Tavera never saw their faces, which were obscured by masks with antlers. Verbal communication was minimal because their Spanish was limited and Tavera did not speak their indigenous language. Nevertheless, he learned that they were fulfilling a vow to travel around the Mexican countryside for a year. When Tavera encountered the dancers, they were only weeks away from their return back to their waiting families in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. Recognizing the similarity of their pilgrimage to the border-as-destination, Tavera recounts that he asked permission to touch the religious figure of San Judas (Saint Jude) imprinted on the drum. Commonly associated with hopeless causes, Saint Jude is also the patron saint of hope. In his recollection of this meeting, Tavera told me, “I recall the encounter as a sign of protection to my travels from mystical creatures from the border.” Tavera has often discussed the power of portraiture to foster prolonged confrontations of the type that rarely happen in person. With portraits, he said, “people can approach, and look at them, and analyze every little detail: the earrings, the makeup, the hat, the mustache. And, that’s something that unfortunately we don’t do in the street because it is very intrusive. Here, you have the opportunity to look and to analyze.” Oftentimes, close looking reveals the absurdity of the situation. Tavera photographed a married couple, one on each side of the border fence in the small desert town of Jacumba, California. The recent erection of the border fence has complicated their way of life and disrupted familial connections that used to flow more freely across a once invisible border between the U.S. and Mexico. Tavera tells their story: “They used to walk to his mother's house on the Mexican side daily but with the new fence in place he has to travel thirty minutes to the crossing check point and thirty minutes to svhis mom’s place. They have been married for many years and now they have to spend weeks separated by the fence.” The husband rests one hand on the bars and the other affectionately on his wife’s shoulder. Despite the barrier physically separating the couple, Tavera records an intimate moment of communication and exchange. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. In his 1995 collection of short essays, The Crystal Frontier, writer Carlos Fuentes noted that the U.S.-Mexico border is not just a line of demarcation that separates two nations from each other, but rather a site through which people, ideas, and commodities flow. Fuentes wrote, "Properties, customs offices, real estate deals, wealth and power provided by control over an illusory, crystal border, a porous frontier through which each year pass millions of people, ideas, products, in short, everything…” The border wall—always incomplete—stands as a symbolic attempt to control the flow of people, yet it cannot contain the flow of ideas. Tavera’s Borderlands photographs penetrate the physical barrier to foster communication and underscore commonalities across the porous border. Andrea Lepage is associate professor of art history at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The exhibition on the work of Xavier Tavera was held at ProjekTraum FN l'atelier Glidden Wozniak in Friedrichshafen, Germany (July 2018). This reflection by Lepage on Tavera's works will be expanded and translated into German for a future catalogue. Xavier Tavera, Untitled, Borderlands, 2017-18. Images courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. “Haight Street Rat" at Cultivate 7 Twelve in Waco, Texas. Photo by G. James Daichendt , by G. James Daichendt In 2010, the anonymous street artist Banksy went on a promotional campaign installing art in major cities to coincide with the release of his documentary “Exit Through the Gift Shop.” The city of San Francisco was fortunate to be one of his targets and the artist created six stencils during the course of his stay. One particular image from this trip, now known has the “Haight Street Rat,” has become the focus of a 2017 documentary movie and has played a major role in facilitating dialogue about who owns public space, museum politics, artist rights, and the importance of conservation. Brian Greif is the individual who saved the painting from being painted over by the city at the expense of his own pocketbook. Filming the entire process, Grief produced the film “Saving Banksy” that outlines his story of being offered hundreds of thousands of dollars for the work, his unsuccessful attempt to donate it to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the interesting dilemmas one faces when they become responsible for something that is valuable (monetarily and culturally),and how these ideals don’t always correlate. Grief did not to sell that work. Instead he decided to make it available to borrow for public exhibitions. Since he made that choice the rat has traveled quite a bit. Most recently to Waco, Texas, a small town not necessarily known for street art but one that hoped to use the enthusiasm for Banksy to further art education, bring the art community together, and garner momentum to host bigger and better arts experiences in the western town in central Texas. Brian Greif produced the film “Saving Banksy” Courtesy Greif, Bottom Right: Graffiti in Waco, Texas. Bottom Left: James Daichendt lectures on street art at Baylor. Photos courtesy of Daichendt One of the stipulations for exhibiting the Banksy is that it must be free and accessible to the public. The Waco rendition of the exhibition, titled “Writing on the Wall,” was an opportunity for local artists to curate a professional show and to set a higher standard for exhibitions in the area. A mix of education and promotion, local partners including non-profit Creative Waco, the gallery Cultivate 7 Twelve, and curator/painter Ty Nathan Clark included several local artists in the exhibit to showcase regional talent. The exhibit was then complemented with a full slate of educational events that provided language and history for talking about art and street art in particular. In addition to the local art scene, the Baylor University Art Department also collaborated in some educational events and even included the Banksy exhibit in some of their assignments to ensure students engaged with the important concepts of the show. There are also plans to bring additional internationally recognized artists to Waco to install public works. The French artist, Blek Le Rat is scheduled to visit this year and install several works around the city in collaboration with local businesses, an exciting development for the city. The importance of the arts cannot be underestimated through this important time in Waco. While Banksy had a particular motive when creating the “Haight Street Rat” in 2010, he certainly could not have imagined how many lives it would impact. Brian Greif, the collector and aficionado responsible for this momentum, now manages the careers of several street artists and has enjoys this new direction in his life. The city of Waco is equally excited as the local arts community has now been connected with the academic community in a way that has never been realized. Banksy’s appeal as an artist is remarkable especially the recognizability of his name. There is a lot to question regarding the narrative surrounding the “Haight Street Rat” and even the aesthetics of the image itself – after all, it was originally meant to be viewed from a distance high on a rooftop. While it may not be a supreme example of Banksy’s work, it is accessible, and it brings an excitement that makes dialogue about the arts easier. An important lesson in aesthetic education and what we need to do as arts professionals to build and grow our collective audiences. “Haight Street Rat” in original San Francisco situ. G. James Daichendt, Ed.D. is an art critic and author of six books. He serves as Dean of the Colleges at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego. You can read more of his writing at San Diego Tribune. PtD Field Notes: If you are near Waco, you can see “Haight Street Rat” in residence at Cultivate 7 Twelve in the exhibition "Writing on the Wall." It has been extended through Saturday, November 17. An Evening with Brian Greif is now on Friday, November 16. Extra Note: "Saving Banksy" was screened at UNLV in April 2017 with filmmaker Colin Day. The documentary is now streaming at Netflix.

|

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|