|

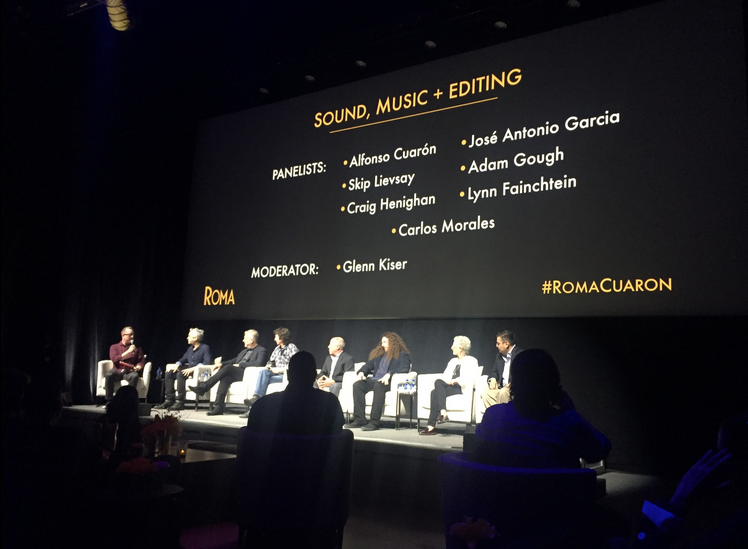

NETFLIX ROMA washes over you from the very first frame: the scrubbing of driveway tiles set against the sights and sounds of Mexico City. Oscar winning director Alfonso Cuarón’s latest film, ROMA, is a NETFLIX limited release. It tells the story of Cleo (played by newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) an indigenous domestic worker in Mexico City’s Roma neighborhood in the early 1970s, and the relationship with the middle-class family that employs her. As Cleo’s life crumbles, so does her employer’s marriage, along with the city surrounding them. When Cleo discovers she is pregnant and the child’s father, Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), abandons her, she confides her predicament to her boss, Sofía (Marina de Tavira.) Expecting to get fired Cleo is surprised Sofia offers help. When the two women face uncertainties side-by-side, the story starts to convey how the nuances of race and class have not disappeared from Mexican society, as well as the underlying political climate that would ultimately transform the country. The early 1970s was a volatile time in Mexico’s capital with its student protests and police massacres. It underscores the characters’ personal upheaval. The sounds of the city and popular music reflecting lost love and poverty almost serve as a warning. Shot in immaculate, grain free black and white and drenched in stunning detail, every inch of the frame reveals a different clue to character, place and story. The NETFLIX feature film release is ideally viewed on the big screen to fully appreciate the silent storytelling throughout. At a ROMA event at Raleigh Studios in December, the director, cast, and key crewmembers shared experiences of their recent collaboration. It all starts with the script. . . sort of. While Cuarón did write a script, he did not make it available to his department heads and talent – sometimes right until close to filming (reminiscent of British director Mike Leigh) - and after much preparation and key decisions were made. The director’s approach was experiential; guiding cast and crew through his personal experience to time and place. He enjoyed long conversations about the Colonia Roma he knew as a child, and sharing his experiences of music, sights and sounds as points of reference for this semi-autobiographical picture. In-sequence shooting over 108 days revealed the story in small bites to cast and crew. The story is rooted in Cuarón’s youth. The character of Cleo is based on Liboria “Libo” Rodriguez, Cuarón’s real-life nanny. Sofía is based on his mother and the other characters include his family as his parents separated. Pepe (Marco Graf) is modeled on Cuarón himself and much of the film is based on his own memories yet seen through Cleo’s eyes. He cast actors and non-actors in key roles, including Aparicio who had just finished training as a school teacher before she was cast as the lead in her first film. The director admitted taking great delight in throwing curveballs. Sometimes he gave each actor a different version of the script, creating a “beautiful chaos” that allowed for improvisation. De Tavira described her surprise at Sofía’s children behaving one way during one take and completely different in the next, all at Cuarón’s direction. All that, plus multiple takes and angles, would later take a toll on Cuarón and editor Adam Gough in post-production. The results are extraordinary. Cuarón’s team recreated a Mexico City that hasn’t been seen in decades. “It’s a dream project for a production designer . . . except for the idea of not having a script.” said production designer Eugenio Caballero. So much of Mexico, including Cuarón’s childhood home, had changed and was unusable as a location. Caballero and set decorator Bárbara Enríquez worked with Cuarón to recreate his original home by using the façade of a house across the street, that was up for demolition, to capture the spirit of the original residence. They even tracked down furniture from Cuarón’s family to use for set pieces. Production worked to make every detail match Cuarón’s memory as close as possible. They found craftsmen to create tiles, as they had been manufactured 70 years ago, to get the authentic look and texture. Every detail – down to drawers that never opened on camera- were filled with specifics at Cuarón’s direction. They even scouted for toys from that era. It gave the director, crew, and talent a sense that everything was real. A major challenge was re-creating Insurgentes Avenue, which now looks nothing like it did in the ‘70s. Azteca Stadium parking lot was not big enough. Production resorted to Google Earth to find a place that had room to recreate the two blocks they needed. That included room to create full storefront sets in case Cuarón wanted to go inside and film an interior scene. The result was mesmerizing, and extended takes were possible. Such as Cleo chasing her young charge down this street on the way to the modern movie theater, which itself was a narrative contrast to the run-down theater the character frequented. Working in black and white, textures and light values also played a key role in every department’s choices. Cuarón served as his own director of photography. Longtime friend and collaborator Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, the original cinematographer, bowed out when the film schedule ran long. Nevertheless Cuarón found Lubezki’s pre-production help invaluable. ROMA panel at Raleigh Studios. Photo by Maria Lopez At the Raleigh event, Lubezki asked, “Why black and white?” For Cuarón it was about Cleo’s character and creating a modern film that looked into the past. “It’s not a vintage black and white. It’s a contemporary black and white.” Replied the director “Black and white was part of the DNA of the film.” True to the film’s DNA, costume designer Anna Terrazas took much into consideration in regards to how wardrobe would work in monochrome. Terrazas often checked with the director to talk over the light values and contrast of fabrics. “One of the things we did was playing with the textures of the clothes,” she said. “Obviously, it was the 70s but again, one thing in Mexico is the 70s wasn’t the 70s in the U.S. We were a little behind the fashion, so that was also a big challenge.” The wardrobe contrasts in the film are apparent not just in Cleo’s clothing, which starts in white then moves into darker shades and finally returns to white in the end. It’s also felt in the Hacienda scene, where the family spends New Year’s with friends. The wardrobe of upper-class Americans and Europeans is a flow of modernity. The clothes of servants speak to the class divide. The plain, older, stiffer styles with their hats and ponchos to fight the cold separate the two worlds aesthetically. The class divide is also apparent in the deadly land disputes mentioned in passing throughout the film. In the end, despite the changes the world around them demands, Cleo’s genuine love for the family, their love for her, and their newly formed bonds do not stop them from the entitlement and sense of obligation that keeps each character from stepping away from the prejudices of race and class. BELOW: Wardrobe and set pieces from ROMA at Raleigh Studios. Photos by Maria Lopez María Margarita López has covered arts and performances for former sister blog, viewfromaloft since 2011. As a film producer, she is co-founder of Ajuua Entertainment, plus consulted and produced media under her company ValorFilms since 2005. To add, her short film, GUILTLESS, was selected to be screened at the CCCM Mexican Center for Culture and Cinematic Arts (Mexican Consulate) on January 10.

0 Comments

Jess Vanessa 'Entre Espinas Florece Esperanza' 2018 Mixed media installation. Photos: PtD "Entre Espinas Florece Esperanza" is the mural and installation by Jess Vanessa created for " ¡Americanx!” at the Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery. It was just painted over. Always a fine writer as well as artist, Jess used Facebook to be poetic about her own work. Her words can easily become an artist statement that carries deeper meaning than the usual declaration from an artist. She graciously granted PtD permission for her thoughts to be shared here. By Jess Vanessa "Entre Espinas Florece Esperanza" is for the voices fighting to be heard, and the piece was dedicated to all members in our community; the documented and undocumented that make up this nation. They, and we, all have one thing in common; being American. Our connections are an intricate weaving of people. When we remove a member of our communities it affects all of us and threatens to unravel the very being of an American community. The current issues on going with deportation affects all of us. Our communities should not, will not, allow any more people to undergo such injustices to have a spirit be unraveled. From these hard times we are like a grain of sand that becomes a pearl; like the cactus growing in the harsh desert heat we will bloom. Like a soon-to-be mother ready to bring new life into this world, there is hope. We carry hope, strength and change for future generations to come. This piece is dedicated to all the Dreamers, those who have been, and are, undocumented. To those whose families have been torn apart, to our refugees, to our immigrants, and to the children of immigrants. To those who are neither from here, nor from there. I want to thank everyone that sent in photographs, for the support, for being there throughout the whole process, and really being a part of this project. I want to thank non-profit organizations such as Make The Road Nevada for doing so much for our communities and being so warm and welcoming. For those interested in becoming more involved with our community Make the road NV is a great local group providing both aide and information as well as keeping informed with ongoing issues in our valley. I encourage all to get up and vote! Thank you! I hope you all enjoyed this piece. Jess Vanessa is an independent Latinx artist born and raised in Las Vegas. Working primarily In painting, drawing, and paper cutting she explores the multiplicity of Xicano identity, empowerment and cultural practices. She has a BFA from UNLV and currently lives and practices her art in Las Vegas, Nevada.

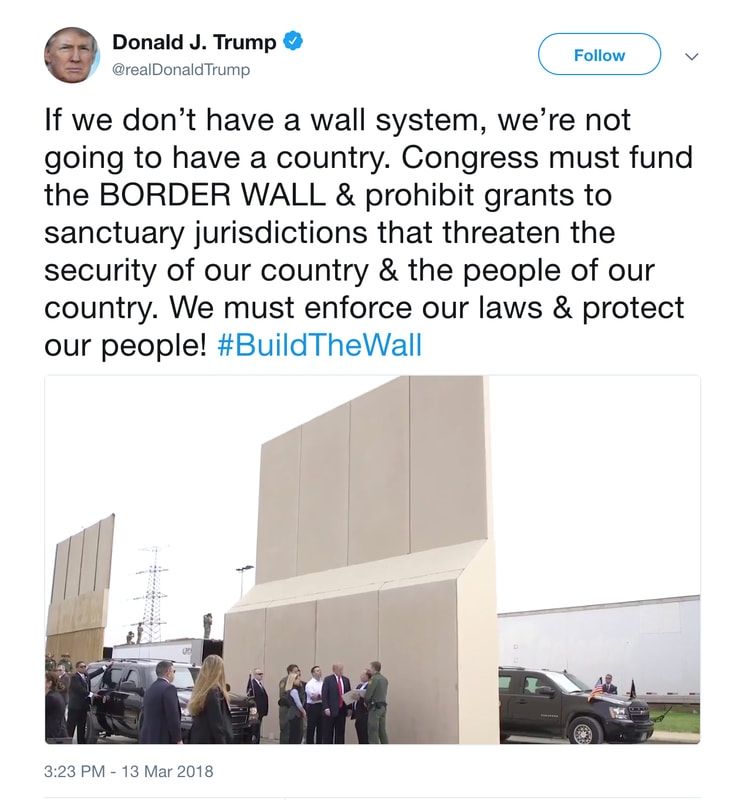

Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. By Andrea Lepage Mexican-born naturalized U.S. citizen, Xavier Tavera (b. 1971) recalls crossing the U.S.-Mexico border a few times with his family as a small child, saying, “I remember the tension and anxiety it produced when my family approached the crossing bridge by car.” Not breaking any laws, Tavera recollects that the family nonetheless waited in uneasy silence until they passed through the checkpoint. Tavera’s memory of crossing underscores the power of the border. The border has—since its inception—functioned as a visible manifestation of the U.S.'s perceived power and political dominance over its southern neighbor. In an interview, Tavera summarized the point: “Mexicans, Latinx and Chicanos—regardless of place of birth and migratory status, and even Latinx living in the U.S. that have never crossed the border—are deeply marked by the notion of border. ‘Border’ is a concept that has defined us symbolically and culturally.” President Donald Trump’s nativist rhetoric combined with his promises to enhance border security and build a border wall have led to increased international focus on the borderlands and those who pass through them. Tavera’s Borderlands series visually explores this territory and also considers the individuals who occupy it. He notes that his conceptualization of the Borderlands series emerged in response to the current administration’s language about the border, explaining, “The abrasive rhetoric that the current government administration has used towards the border has been one of the propelling motivations of this project.” The Borderlands photographs seek to mitigate the detrimental effects of such speech on Latinx communities by engineering close encounters with these individuals who occupy the region and by proposing imaginary alternatives to the border wall. Tavera took his first of three trips to the U.S.-Mexico border in January of 2017, intending to document the surrounding borderlands and to examine the border wall. Following its path, Tavera revisited the border in May of 2017 and again in March of 2018. He expects to return at least three more times to bring the Borderlands project to completion. During these trips, Tavera alters the photographed landscapes by digitally superimposing tables, tunnels, or shelters on the desolate terrain. In considering the possible use of these imaginary projects by unpictured communities, Tavera asked, “Would we find commonalities or differences in a given space? What would be the risks of communication and involvement with a different culture or community?” Tavera’s phrasing provides a counterpoint to Trump’s frequent anti-immigrant statements that emphasize difference and reject the possibility of cross-cultural commonality. Trump’s March 13, 2018 tweet—issued during Tavera’s third trip to the border—is representative of the U.S. president’s fear-inducing rhetoric: Tavera’s series visually rejects speech that casts the children and adults who cross the border with or without authorization as threats to U.S. citizens. Instead, the artist conceptualizes the border as a scar across the rugged landscape, a characterization that evokes Chicana theorist Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1987 description of the border in her seminal text Borderlands/La Frontera. Anzaldúa defined the border as both an injurious and injured site, “una herida abierta [an open wound] where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.” Extending Anzaldúa’s metaphor to the physical border barrier, Tavera concludes that "the political character of this open wound materializes in a wall with sentiments of nationalism, protectionism and absurdity.” Like Robert Misrach’s Border Cantos photographs, many of Tavera’s Borderlands images are unpopulated, revealing only the residues of human presence, and even those traces appear unwelcome. One of Tavera’s photographs centers on a set of chained tires of the kind that would be dragged behind U.S. border patrol trucks to smooth out the terrain. The procedure, variously called “pulling the drag,” “sign cutting,” or “cutting for sign,” allows border patrol agents to identify new footprints to track and capture migrants. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. Tavera’s photographs are part of an upsurge of border-related artwork produced since 2006, the year when then-president George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act. The bill sought to restrict passage across the border using systematic human and drone surveillance and through the creation of reinforced fencing. In one of his photographs, Tavera captures a surveillance blimp apparently preparing for flight under the cover of night. The star-like lights surrounding the blimp penetrate the pitch black landscape, serving as absurd beacons of protectionism amidst the expanse of the borderlands. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera.

Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. "What I like about portraiture," Tavera said, "is the contact with the people.” In a 2016 interview, Tavera discussed the power of the camera to grant him access to people and to open a metaphorical window into their lives. He underscores that “the main purpose of this is to try to understand, not to make assumptions” about the sitters. Despite Trump’s attempt to conjure up the false image of an army of Mexicans ready to overtake the border, the U.S. is not a coveted destination for all. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. Tavera photographed three dancers on the streets of Nogales, Mexico, for example, who had no intention of crossing the border. Like Tavera, it was, instead, their destination. The dancers carried drums and each wore rattles crafted from empty bullet shells. In the course of their brief exchange, Tavera never saw their faces, which were obscured by masks with antlers. Verbal communication was minimal because their Spanish was limited and Tavera did not speak their indigenous language. Nevertheless, he learned that they were fulfilling a vow to travel around the Mexican countryside for a year. When Tavera encountered the dancers, they were only weeks away from their return back to their waiting families in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. Recognizing the similarity of their pilgrimage to the border-as-destination, Tavera recounts that he asked permission to touch the religious figure of San Judas (Saint Jude) imprinted on the drum. Commonly associated with hopeless causes, Saint Jude is also the patron saint of hope. In his recollection of this meeting, Tavera told me, “I recall the encounter as a sign of protection to my travels from mystical creatures from the border.” Tavera has often discussed the power of portraiture to foster prolonged confrontations of the type that rarely happen in person. With portraits, he said, “people can approach, and look at them, and analyze every little detail: the earrings, the makeup, the hat, the mustache. And, that’s something that unfortunately we don’t do in the street because it is very intrusive. Here, you have the opportunity to look and to analyze.” Oftentimes, close looking reveals the absurdity of the situation. Tavera photographed a married couple, one on each side of the border fence in the small desert town of Jacumba, California. The recent erection of the border fence has complicated their way of life and disrupted familial connections that used to flow more freely across a once invisible border between the U.S. and Mexico. Tavera tells their story: “They used to walk to his mother's house on the Mexican side daily but with the new fence in place he has to travel thirty minutes to the crossing check point and thirty minutes to svhis mom’s place. They have been married for many years and now they have to spend weeks separated by the fence.” The husband rests one hand on the bars and the other affectionately on his wife’s shoulder. Despite the barrier physically separating the couple, Tavera records an intimate moment of communication and exchange. Courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. In his 1995 collection of short essays, The Crystal Frontier, writer Carlos Fuentes noted that the U.S.-Mexico border is not just a line of demarcation that separates two nations from each other, but rather a site through which people, ideas, and commodities flow. Fuentes wrote, "Properties, customs offices, real estate deals, wealth and power provided by control over an illusory, crystal border, a porous frontier through which each year pass millions of people, ideas, products, in short, everything…” The border wall—always incomplete—stands as a symbolic attempt to control the flow of people, yet it cannot contain the flow of ideas. Tavera’s Borderlands photographs penetrate the physical barrier to foster communication and underscore commonalities across the porous border. Andrea Lepage is associate professor of art history at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The exhibition on the work of Xavier Tavera was held at ProjekTraum FN l'atelier Glidden Wozniak in Friedrichshafen, Germany (July 2018). This reflection by Lepage on Tavera's works will be expanded and translated into German for a future catalogue. Xavier Tavera, Untitled, Borderlands, 2017-18. Images courtesy of the artist. © Xavier Tavera. |

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|