|

Clarice in Downtown Las Vegas Photo: Ed Fuentes Not many in Las Vegas consider Clarice Tara Cuda the kind of artist who needs encouragement. Anyone who keeps track of the local art scene has seen her work and she can be considered one of the wisest artist who has landed in town recently.

It came after hard thinking and listening to herself. In fact, you can feel her listening to you as she studies your gestures, sometimes glancing away to break from eye contact briefly, then quickly return to create an honest moment. Like describing herself as someone who once missed making art and decided to take her work seriously. That came after some reflection. “I knew in my heart that…” she starts to say, as if a reluctant confession was about to escape her “I know I didn’t put in the work.” Then she beams a smile that says she knows art is about curating moments. Clarice reintroduced herself to her inner creator by working in a tattoo shop where she revisited her skills in capturing the details of forms and shapes. Then she worked a desk at a local gallery. That also helped. It was there she displayed her, what was then new work, and met the local art community one person at a time. She had courses at CSN and UNLV. Clarice says it was a UNLV sculpture class that changed the way she produced ideas. Also, it was there she began to understand how a body, hers, could be an art subject, not object, infiltrating physical space that details her personal philosophy. Right after earning her BFA she changed the expectations of a growing clan of followers with “Dissonance,” a performance of live binding with fish line that was a spiritual declaration of “taking away the traditional concepts of beauty in the body.” Despite her constant weaving of ideas and materials, Clarice is consistent. She challenges outdated declarations of beauty. That was seen recently by her wearing a 1950-ish outfit while lights bathed her in pinks and blues, all symbols of gender roles, while posed behind a display window of a former retail store. It was a concept and performance that came from a collaboration with Amanda Keating. People stepped up to the quiet spectacle and were encouraged to replicate gestures; an intimate mirroring of movement. For the artists, it was about moving past pain and love by using small gentle slow gestures that quietly coaxed and dared viewers to mirror emotions. Sometimes she allowed them to take the lead, which she gave them, so she can gently take it back. Then it was kept in a safe place for both. Some want to infiltrate the physical and emotional space. They couldn’t. A barrier was there; a thick glass window. That was at “Still Life” for Art Basel in Miami produced for Raw Pop Up. Just this year. Art Basel. Clarice is not yet 30. Only a few years ago her creative space was a tattoo parlor. Now she protects her art within a protocol of performance, a safe barrier that allows her eyes to listen.

0 Comments

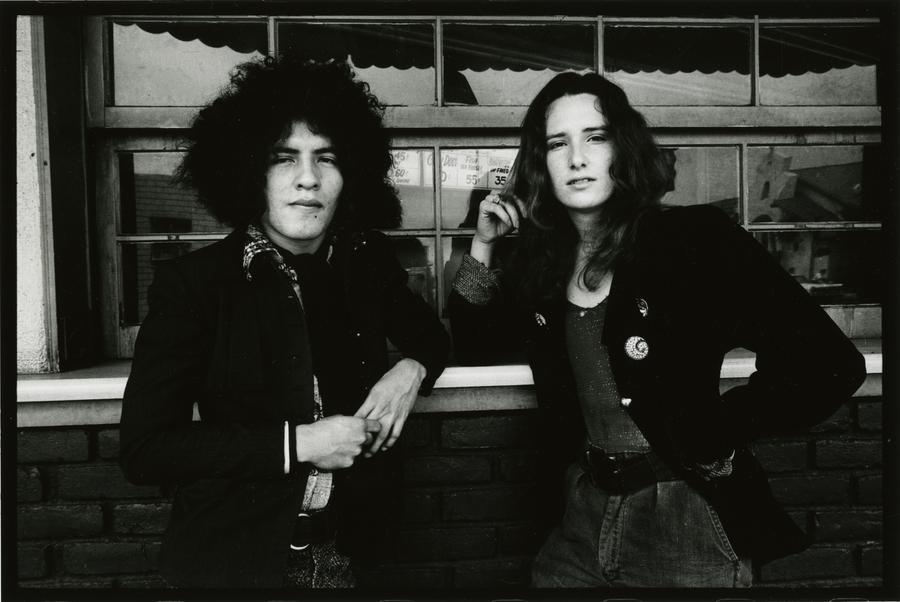

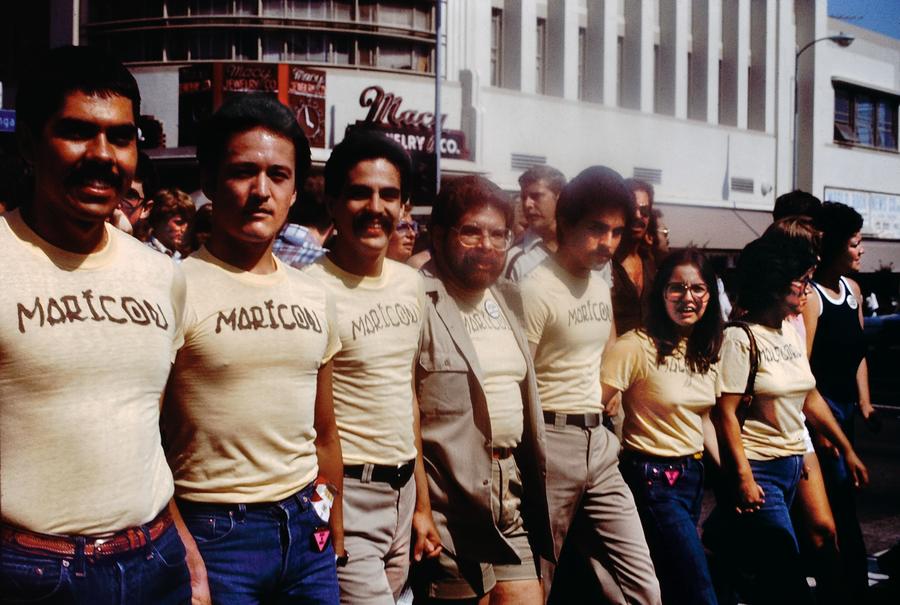

Anthony Friedkin, Jim and Mundo, Montebello, East Los Angeles, 1972. From The Gay Essay, 1969–73. Gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 in. Gift of Anthony Friedkin. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Courtesy of Anthony Friedkin This is art that speaks, screams, and whispers from behind the complex layered nature of being a queer Chicanx artist living and working in a Los Angeles of another time. Soon you will be able to mingle with 150 of those works from fifty artists created during an era when it was dangerous for them to be themselves. “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” is curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz and now on a U.S. tour will make a stop at the UNLV Barrick Museum of Art. Early research for “Axis Mundo” became an excavation of artworks showing how the beginning of the Chicano Movement had help beyond marching and protesting. More help came from a network of painters, photographers, and performers who found solidarity with each other and produced art laced with an early queer aesthetic that challenged the ideas of art and identity during the late 1960s and through the early '90s. Any Chicanx artist working solo outside mainstream cultural circles would not come close to making social change, much less anyone with sexuality badges. These artists tried to do it together. They were cued by the Chicano Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, jumped in to support Gay Activism during the 1970s, and then created art against a backdrop of AIDS awareness in the 1980s and 1990s. Now the works are tagged with scholarship that speaks to the radical use of genres, venues, and mediums. It is not just exploration of a lost art movement, or a sentimental homage that orbits around a central figure. “Axis Mundo” adds context to a regional avant-garde working within sub-cultures isolated from social and art institutions. Mundo does connect with a symbolic figurehead; a visible mascot for the creative free-for-all. It is the not-so-well-known artist Edmundo “Mundo” Meza, born in Tijuana in 1955, who died of complications due to AIDS in 1985. Meza migrated to the U.S. to be raised in East Los Angeles and was a painter turned performance artist, then played with the iconography and function of fashion, and used window displays for site-specific installations. He collaborated with other East L.A. artists by approaching art-making as a multidisciplinary practice. “Axis Mundo” is word-play on axis mundi, the cosmic connection between earth, heaven and hell. With “mundo” switching out “mundi” there is a linguistic transference from Latin to Spanglish. By using Meza as a namesake, curators Chavoya and Frantz use mundo as an eponym for the social solidarity between low and high-profile Chicanx artists. “It was amazing curatorship. I don’t know how they found the images,” says Judith Baca, whose work is featured in the exhibition. “There’s stuff that I haven’t been seen in years. They dug images up from the past.” Knowing the soul of “Axis Mundo” is understanding how the mash-up of styles and artists are still informing, or competing, with each other, grappling for identity while dodging established “-isms.” That is the virtuosity in this ephemeral mix of materials and lifestyle. Some works are as simple as mail cards printed to be distributed to those living in East L.A. proper, or t-shirts with street smart declarations, all made possible because low cost reproduction infiltrated graphic arts. Printed pieces become high concept messaging made possible by what is now considered lo-fi technology. That allowed ideas that bent expectations of identity, while calling out for civil rights or later speaking out against a government's apathy to the AIDS crisis, to be assembled with dexterity. The walls the artist faced were not just homophobia or closed doors of art institutions. Being Mexican-American often meant being raised Catholic, more of a cultural assignment than spirituality choice, and some works respond to the Brown Church. You can sense how a few makers of queer Chicanx art were conflicted as they sought to maintain artistic rebellion with personal faith. Back then, art by Mexican-Americans was often dismissed, unless it had folk art prompts or was painted on an inner-city wall. Those artists were not considered suitable candidates for art academia or able to engineer broad conceptual ideas. It was a different world then and there were other stigmas, recalls Baca, adding it was just dangerous to be queer. “The White male (artist) could be ‘out’ without impunity,” she says. You can see that when one considers artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, who was free to push themes. Yet, gifted painter Carlos Almaraz had his sexuality stored in a conditional state of being; being Gay was as underground as being Chicano. “The word 'Gay' is a White male invention. Oscar Wilde, to me, is its inventor,” says Gronk (born Glugio Nicandro), the painter, conceptual artist, and founding member of the art collective ASCO. He also has works in the exhibition. Gronk deems “Axis Mundo” is testament that the American avant-garde underground was not reserved for Whites Only. This was the West Coast edition of artists sharing the experience of visual experimentation, partying, locked in conflict and embrace, all while making art beyond painting, as practiced at Andy Warhol's The Factory. “It has painting for sure,” says Gronk. “But a lot of the work was concept based, like mail art, and graphics.” Instead of housed in a Manhattan loft, the centralized social state of the mundo-minded was East Los. Judith F. Baca, Documentation of Vanity Table, a performance for the exhibition Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer at the Woman’s Building, September 1976. Woman’s Building Records. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Judith F. Baca. “We were bending everything back then,” says Baca, who is featured in photographs that had her portray a confident Chola, staring back, or ignoring a camera lens, in 1970s document of Pachuca visual identity, where fashion, hair, eye make-up and attitude were codes for defiance. The series was her 1976 performance “Vanity Table” for “Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer” at the Woman’s Building, home of the influential Feminist Studio Workshop. The touting of “Axis Mundo” leans to being about landmark engagement by male and female queer artists within L.A’s Chicano culture using the spirit of Meza as a banner of alternative creativity. Still, while queerness is the true center of the exhibit, the scared site, the axis mundi; sexuality was not the focus or obsession of all the artists. “There are so many other words that describe sexual orientation,” says Gronk. “I don't use any and I really don't care what word is used. Call me ‘Artist’.” Fundamentally the networking a way to give each other support while each person explored how to dedicate an art affinity to be intimate with. “I thought of myself as a feminist, and muralist,” says Baca. “Social justice was my primary identify.” Thankfully, "Axis Mundo” pulls back on references to campy aesthetic. The exhibition is more than a display of artifacts with historic civil rights themes, or the memory of artists wanting to simply exist through their work. By taking the works on the road, from L.A. to Colorado, then New York, now Las Vegas, and soon Texas, curators Chavoya and Frantz clarify the long-standing legacy was the networking. By distributing information to like-minded masses and new eyes, "Axis Mundo” stands in for the 'zines and mail cards once sent to other artists producing visual experiences informed by queerness and ethnicity. That allows more passage across the borders of contemporary American art without apology, and (almost) without drama; to be transitional so others will consider producing works with the new dare and flair. It also states being a Chicanx queer thinker, which was a once a stigma, can be treated as a matter-of-art-fact. Or as Baca says, "Now it's 'Yes . . and?'" Participants in the Christopher Street West Pride parade wearing Joey Terrill’s malflora and maricón T-shirts, June 1976. Terrill appears third from the left. Photo by Teddy Sandoval. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas.

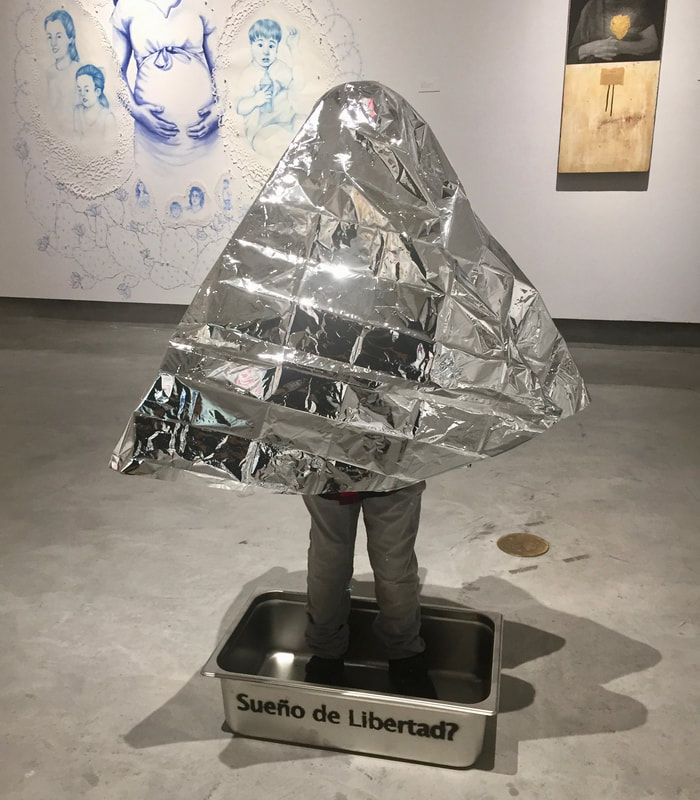

“Security Blanket” (2018) by Luis Varela-Rico in “¡Americanx!” at Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery. An artist snuck a child past the borders of academic infused art. It was “Security Blanket” (2018) by Luis Varela-Rico, as seen during the run of “¡Americanx!” at Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery from October 1 through November 21. That was the lone figure standing in the midst of visual conversations by other artists, many who graduated from UNLV, or teach within the Nevada Higher Education system. “Security Blanket” was one of a number of art objects seen in “¡Americanx!” Varela-Rico’s sculpture, or installation, can be read as a small boy, a safe presumption by the diminutive size and smaller version of an outfit that refers to male field workers, and what is worn during late-night migration to the U.S. The piece spoke not just to policy, but the collective experience of watching televised news reports of minors separated from parents attempting to cross the border into the U.S. Varela-Rico keeps the topic visible, even as attention of left-behind children has slipped away due the noise of White House policy and tweeting. Varela-Rico’s art wasn't just an artist’s interpretation of slipping in unnoticed. This entry came in after the opening. It was a late add. Not from disenchantment by the artist of being part of the exhibition, but having to work through a busy schedule of producing large-scale public art sculptures. Yet, in its simplicity, “Security Blanket” added a needed bite of social-justice-authenticity to “¡Americanx!” On the small figure a plaid workmen shirt is just visible, so clothing becomes code for seeking labor. The pattern and material is often worn by immigrants to cope with the weather, and a subtle wardrobe item that refers to protection. There is the obvious symbol of protection; an emergency thermal blanket, as those supplied when children are in holding pens. The “boy” stood inside an industrial steam table pan. That the only part of this work that was unclear. (1) One cannot tell it was meant to be reference as an anticipated tool of kitchen prep, an implied barrier to the art, or a thread to the artist’s previous works in metal. What is clear was the writing on the pan, Sueno de Libertad, or “Dream of Freedom.” With “Security Blanket” positioned in the open space of the gallery it gained deeper meaning when viewed with “Entre Espinas Florece Esperanza” in the background. Jess Vanessa’s mural featuring an expectant mother added a reference to others who may be affected by the politics Varela-Rico is referring to. On its own “Security Blanket” is an emblem of the political wall built from ongoing GOP campaign promises made to red states and is a comment to the mandates pushed forth by Stephen Miller, the political advisor of current immigration policies. Miller has been accused as being an advisor of hate and isolation, a hunter that uses gestures of authority, like having children confiscated from anyone attempting to enter the country with them if they do not adhere to his interpretation of immigration law. That method became a warning shot and talking point: Dreaming of freedom may cost you your child. The installation, or sculpture, made of real objects and clothing is a dream interrupted. The child is made anonymous by a thermal blanket over his head, and he waits to be shuffled off next by immigration authorities. The piece, and its relationship to other works in the exhibition stayed on my mind after “¡Americanx!” closed. Always present in Varela-Rico’s work is a committed to craft that can be complicit to cultural systems that intersect in unexpected places. His metal origami birds hung on random power lines was a form of street art infiltration. Near the City of Las Vegas City Hall, a pair of 16-foot stainless steel forms are framed as Southern Paiute baskets, a public art reminder of the original administrators of the region. “Security Blanket” political statement is an powerful use of a collective conscience that shared the larger media experience of seeing footage of children lined up like small prisoners steered into U.S. makeshift facilities. The work reminds us that minors are still a symbiosis between a voting base and a White House administration. All of the artworks on view revealed how social and political commentary is the readymade for Latino/a/x artists. In this piece we are reminded of the aftermath of legislation can change a person from its original function, to hope and dream, into an object controlled by those who enforce policy. Legs visible under the silver that reflects sun and light, the artist may also be saying that the government use of shiny objects distracted some to think children were being cared for. That had the work give larger context in this exhibition of works by local Latino artist who had different experiences living in the American West. The child, and the family that brought him here, wanted to be part of that experience. Here he is portrayed as being hidden in plain sight and unable to witness the conversations around him. The young prisoner of politics is patiently waiting to be shuffled into the next room. (1) Luis Varela-Rico writes in to say "The steel container, which had an American flag sticker on it, was meant to represent being contained within metal." 'Radial Symmetry'

|

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|