|

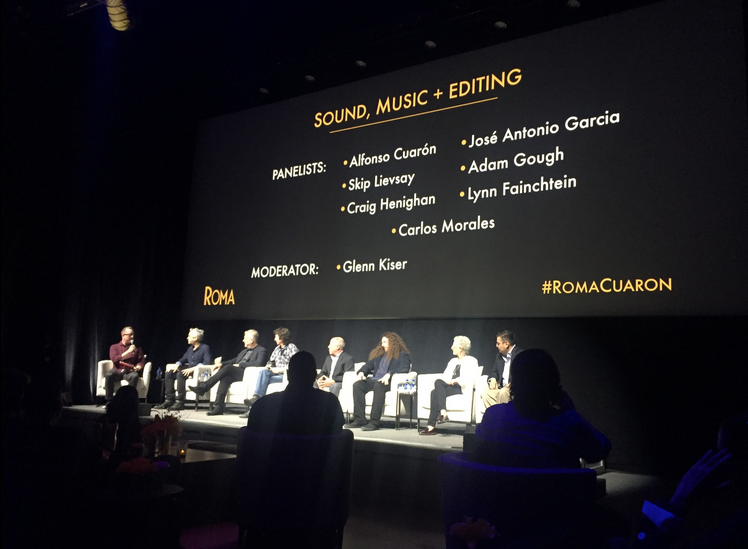

NETFLIX ROMA washes over you from the very first frame: the scrubbing of driveway tiles set against the sights and sounds of Mexico City. Oscar winning director Alfonso Cuarón’s latest film, ROMA, is a NETFLIX limited release. It tells the story of Cleo (played by newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) an indigenous domestic worker in Mexico City’s Roma neighborhood in the early 1970s, and the relationship with the middle-class family that employs her. As Cleo’s life crumbles, so does her employer’s marriage, along with the city surrounding them. When Cleo discovers she is pregnant and the child’s father, Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), abandons her, she confides her predicament to her boss, Sofía (Marina de Tavira.) Expecting to get fired Cleo is surprised Sofia offers help. When the two women face uncertainties side-by-side, the story starts to convey how the nuances of race and class have not disappeared from Mexican society, as well as the underlying political climate that would ultimately transform the country. The early 1970s was a volatile time in Mexico’s capital with its student protests and police massacres. It underscores the characters’ personal upheaval. The sounds of the city and popular music reflecting lost love and poverty almost serve as a warning. Shot in immaculate, grain free black and white and drenched in stunning detail, every inch of the frame reveals a different clue to character, place and story. The NETFLIX feature film release is ideally viewed on the big screen to fully appreciate the silent storytelling throughout. At a ROMA event at Raleigh Studios in December, the director, cast, and key crewmembers shared experiences of their recent collaboration. It all starts with the script. . . sort of. While Cuarón did write a script, he did not make it available to his department heads and talent – sometimes right until close to filming (reminiscent of British director Mike Leigh) - and after much preparation and key decisions were made. The director’s approach was experiential; guiding cast and crew through his personal experience to time and place. He enjoyed long conversations about the Colonia Roma he knew as a child, and sharing his experiences of music, sights and sounds as points of reference for this semi-autobiographical picture. In-sequence shooting over 108 days revealed the story in small bites to cast and crew. The story is rooted in Cuarón’s youth. The character of Cleo is based on Liboria “Libo” Rodriguez, Cuarón’s real-life nanny. Sofía is based on his mother and the other characters include his family as his parents separated. Pepe (Marco Graf) is modeled on Cuarón himself and much of the film is based on his own memories yet seen through Cleo’s eyes. He cast actors and non-actors in key roles, including Aparicio who had just finished training as a school teacher before she was cast as the lead in her first film. The director admitted taking great delight in throwing curveballs. Sometimes he gave each actor a different version of the script, creating a “beautiful chaos” that allowed for improvisation. De Tavira described her surprise at Sofía’s children behaving one way during one take and completely different in the next, all at Cuarón’s direction. All that, plus multiple takes and angles, would later take a toll on Cuarón and editor Adam Gough in post-production. The results are extraordinary. Cuarón’s team recreated a Mexico City that hasn’t been seen in decades. “It’s a dream project for a production designer . . . except for the idea of not having a script.” said production designer Eugenio Caballero. So much of Mexico, including Cuarón’s childhood home, had changed and was unusable as a location. Caballero and set decorator Bárbara Enríquez worked with Cuarón to recreate his original home by using the façade of a house across the street, that was up for demolition, to capture the spirit of the original residence. They even tracked down furniture from Cuarón’s family to use for set pieces. Production worked to make every detail match Cuarón’s memory as close as possible. They found craftsmen to create tiles, as they had been manufactured 70 years ago, to get the authentic look and texture. Every detail – down to drawers that never opened on camera- were filled with specifics at Cuarón’s direction. They even scouted for toys from that era. It gave the director, crew, and talent a sense that everything was real. A major challenge was re-creating Insurgentes Avenue, which now looks nothing like it did in the ‘70s. Azteca Stadium parking lot was not big enough. Production resorted to Google Earth to find a place that had room to recreate the two blocks they needed. That included room to create full storefront sets in case Cuarón wanted to go inside and film an interior scene. The result was mesmerizing, and extended takes were possible. Such as Cleo chasing her young charge down this street on the way to the modern movie theater, which itself was a narrative contrast to the run-down theater the character frequented. Working in black and white, textures and light values also played a key role in every department’s choices. Cuarón served as his own director of photography. Longtime friend and collaborator Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, the original cinematographer, bowed out when the film schedule ran long. Nevertheless Cuarón found Lubezki’s pre-production help invaluable. ROMA panel at Raleigh Studios. Photo by Maria Lopez At the Raleigh event, Lubezki asked, “Why black and white?” For Cuarón it was about Cleo’s character and creating a modern film that looked into the past. “It’s not a vintage black and white. It’s a contemporary black and white.” Replied the director “Black and white was part of the DNA of the film.” True to the film’s DNA, costume designer Anna Terrazas took much into consideration in regards to how wardrobe would work in monochrome. Terrazas often checked with the director to talk over the light values and contrast of fabrics. “One of the things we did was playing with the textures of the clothes,” she said. “Obviously, it was the 70s but again, one thing in Mexico is the 70s wasn’t the 70s in the U.S. We were a little behind the fashion, so that was also a big challenge.” The wardrobe contrasts in the film are apparent not just in Cleo’s clothing, which starts in white then moves into darker shades and finally returns to white in the end. It’s also felt in the Hacienda scene, where the family spends New Year’s with friends. The wardrobe of upper-class Americans and Europeans is a flow of modernity. The clothes of servants speak to the class divide. The plain, older, stiffer styles with their hats and ponchos to fight the cold separate the two worlds aesthetically. The class divide is also apparent in the deadly land disputes mentioned in passing throughout the film. In the end, despite the changes the world around them demands, Cleo’s genuine love for the family, their love for her, and their newly formed bonds do not stop them from the entitlement and sense of obligation that keeps each character from stepping away from the prejudices of race and class. BELOW: Wardrobe and set pieces from ROMA at Raleigh Studios. Photos by Maria Lopez María Margarita López has covered arts and performances for former sister blog, viewfromaloft since 2011. As a film producer, she is co-founder of Ajuua Entertainment, plus consulted and produced media under her company ValorFilms since 2005. To add, her short film, GUILTLESS, was selected to be screened at the CCCM Mexican Center for Culture and Cinematic Arts (Mexican Consulate) on January 10.

0 Comments

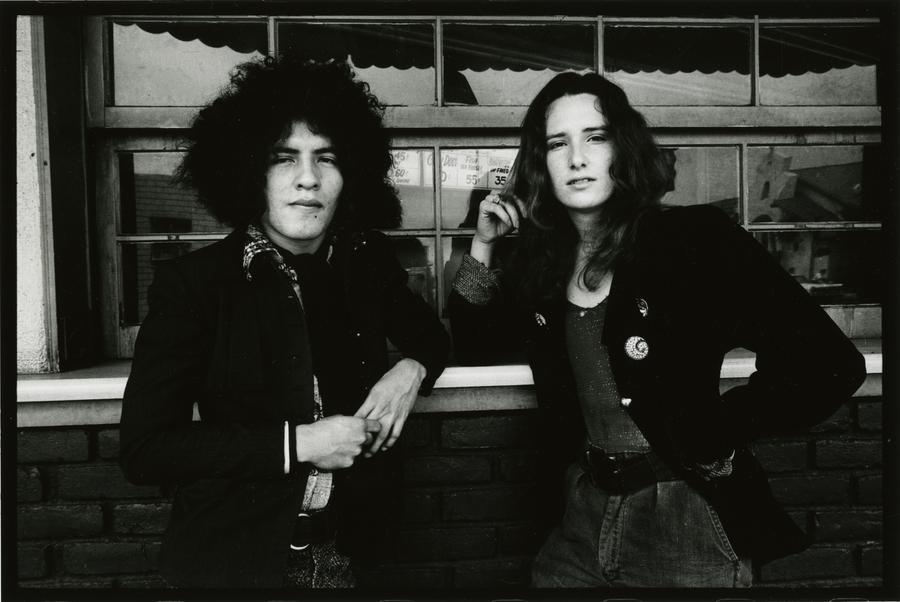

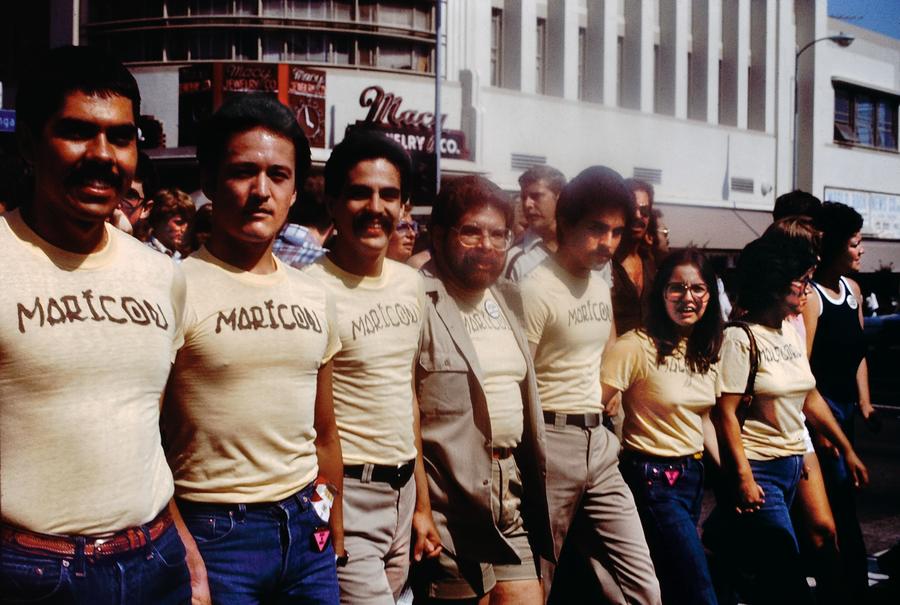

Anthony Friedkin, Jim and Mundo, Montebello, East Los Angeles, 1972. From The Gay Essay, 1969–73. Gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 in. Gift of Anthony Friedkin. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Courtesy of Anthony Friedkin This is art that speaks, screams, and whispers from behind the complex layered nature of being a queer Chicanx artist living and working in a Los Angeles of another time. Soon you will be able to mingle with 150 of those works from fifty artists created during an era when it was dangerous for them to be themselves. “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” is curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz and now on a U.S. tour will make a stop at the UNLV Barrick Museum of Art. Early research for “Axis Mundo” became an excavation of artworks showing how the beginning of the Chicano Movement had help beyond marching and protesting. More help came from a network of painters, photographers, and performers who found solidarity with each other and produced art laced with an early queer aesthetic that challenged the ideas of art and identity during the late 1960s and through the early '90s. Any Chicanx artist working solo outside mainstream cultural circles would not come close to making social change, much less anyone with sexuality badges. These artists tried to do it together. They were cued by the Chicano Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, jumped in to support Gay Activism during the 1970s, and then created art against a backdrop of AIDS awareness in the 1980s and 1990s. Now the works are tagged with scholarship that speaks to the radical use of genres, venues, and mediums. It is not just exploration of a lost art movement, or a sentimental homage that orbits around a central figure. “Axis Mundo” adds context to a regional avant-garde working within sub-cultures isolated from social and art institutions. Mundo does connect with a symbolic figurehead; a visible mascot for the creative free-for-all. It is the not-so-well-known artist Edmundo “Mundo” Meza, born in Tijuana in 1955, who died of complications due to AIDS in 1985. Meza migrated to the U.S. to be raised in East Los Angeles and was a painter turned performance artist, then played with the iconography and function of fashion, and used window displays for site-specific installations. He collaborated with other East L.A. artists by approaching art-making as a multidisciplinary practice. “Axis Mundo” is word-play on axis mundi, the cosmic connection between earth, heaven and hell. With “mundo” switching out “mundi” there is a linguistic transference from Latin to Spanglish. By using Meza as a namesake, curators Chavoya and Frantz use mundo as an eponym for the social solidarity between low and high-profile Chicanx artists. “It was amazing curatorship. I don’t know how they found the images,” says Judith Baca, whose work is featured in the exhibition. “There’s stuff that I haven’t been seen in years. They dug images up from the past.” Knowing the soul of “Axis Mundo” is understanding how the mash-up of styles and artists are still informing, or competing, with each other, grappling for identity while dodging established “-isms.” That is the virtuosity in this ephemeral mix of materials and lifestyle. Some works are as simple as mail cards printed to be distributed to those living in East L.A. proper, or t-shirts with street smart declarations, all made possible because low cost reproduction infiltrated graphic arts. Printed pieces become high concept messaging made possible by what is now considered lo-fi technology. That allowed ideas that bent expectations of identity, while calling out for civil rights or later speaking out against a government's apathy to the AIDS crisis, to be assembled with dexterity. The walls the artist faced were not just homophobia or closed doors of art institutions. Being Mexican-American often meant being raised Catholic, more of a cultural assignment than spirituality choice, and some works respond to the Brown Church. You can sense how a few makers of queer Chicanx art were conflicted as they sought to maintain artistic rebellion with personal faith. Back then, art by Mexican-Americans was often dismissed, unless it had folk art prompts or was painted on an inner-city wall. Those artists were not considered suitable candidates for art academia or able to engineer broad conceptual ideas. It was a different world then and there were other stigmas, recalls Baca, adding it was just dangerous to be queer. “The White male (artist) could be ‘out’ without impunity,” she says. You can see that when one considers artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, who was free to push themes. Yet, gifted painter Carlos Almaraz had his sexuality stored in a conditional state of being; being Gay was as underground as being Chicano. “The word 'Gay' is a White male invention. Oscar Wilde, to me, is its inventor,” says Gronk (born Glugio Nicandro), the painter, conceptual artist, and founding member of the art collective ASCO. He also has works in the exhibition. Gronk deems “Axis Mundo” is testament that the American avant-garde underground was not reserved for Whites Only. This was the West Coast edition of artists sharing the experience of visual experimentation, partying, locked in conflict and embrace, all while making art beyond painting, as practiced at Andy Warhol's The Factory. “It has painting for sure,” says Gronk. “But a lot of the work was concept based, like mail art, and graphics.” Instead of housed in a Manhattan loft, the centralized social state of the mundo-minded was East Los. Judith F. Baca, Documentation of Vanity Table, a performance for the exhibition Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer at the Woman’s Building, September 1976. Woman’s Building Records. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Judith F. Baca. “We were bending everything back then,” says Baca, who is featured in photographs that had her portray a confident Chola, staring back, or ignoring a camera lens, in 1970s document of Pachuca visual identity, where fashion, hair, eye make-up and attitude were codes for defiance. The series was her 1976 performance “Vanity Table” for “Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer” at the Woman’s Building, home of the influential Feminist Studio Workshop. The touting of “Axis Mundo” leans to being about landmark engagement by male and female queer artists within L.A’s Chicano culture using the spirit of Meza as a banner of alternative creativity. Still, while queerness is the true center of the exhibit, the scared site, the axis mundi; sexuality was not the focus or obsession of all the artists. “There are so many other words that describe sexual orientation,” says Gronk. “I don't use any and I really don't care what word is used. Call me ‘Artist’.” Fundamentally the networking a way to give each other support while each person explored how to dedicate an art affinity to be intimate with. “I thought of myself as a feminist, and muralist,” says Baca. “Social justice was my primary identify.” Thankfully, "Axis Mundo” pulls back on references to campy aesthetic. The exhibition is more than a display of artifacts with historic civil rights themes, or the memory of artists wanting to simply exist through their work. By taking the works on the road, from L.A. to Colorado, then New York, now Las Vegas, and soon Texas, curators Chavoya and Frantz clarify the long-standing legacy was the networking. By distributing information to like-minded masses and new eyes, "Axis Mundo” stands in for the 'zines and mail cards once sent to other artists producing visual experiences informed by queerness and ethnicity. That allows more passage across the borders of contemporary American art without apology, and (almost) without drama; to be transitional so others will consider producing works with the new dare and flair. It also states being a Chicanx queer thinker, which was a once a stigma, can be treated as a matter-of-art-fact. Or as Baca says, "Now it's 'Yes . . and?'" Participants in the Christopher Street West Pride parade wearing Joey Terrill’s malflora and maricón T-shirts, June 1976. Terrill appears third from the left. Photo by Teddy Sandoval. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas.

Installation view of Vincent Valdez: The City at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, 2018. Purchase through the generosity of Guillermo C. Nicolas and James C. Foster in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, with additional support from Jeanne and Michael Klein and Ellen Susman in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2017. © Vincent Valdez Revisiting Vincent Valdez’s The City: Critical Moments of Silence and Reflection in Times of Distortion and Chaos By ANDREA LEPAGE Vincent Valdez’s “The City” has received a wide array of media coverage since its opening at the Blanton Museum of Art on July 17, 2018. In October 2016, I wrote a piece for PaintThisDesert when "The City" was on view at the David Shelton Gallery in Houston, Texas. Since then, the Blanton Museum of Art (UT Austin) purchased Valdez’s 30-foot-long painting depicting fourteen members of the Ku Klux Klan who stand in as allegorical representations of a longstanding and prevailing system of white supremacy in the United States. The hooded baby—cradled in a mother’s arms—leaves the viewer with the uncomfortable reminder that hate is transmitted seamlessly from one generation to the next. The intimidating hooded figures loom larger-than-life over the viewer and nearly obscure the distant gleaming city from which the composition takes its name. I pointed out in an essay written for the Blanton Museum’s gallery guide that Valdez’s painting calls for a visual comparison between overt and easily recognizable forms of racism (the Klan) and more covert and hidden forms (the city plan). Valdez’s inscription, “For PG & GSH,” located in the lower right corner acknowledges the prevalence of both manifestations. In paying homage to Philip Guston’s 1969 “City Limits” and Gil Scott-Heron’s 1980 visceral rendition of The Klan, Valdez inserts himself into a multi-generational artistic lineage alongside a painter and a musician who also opposed the Klan and their ideology. Vincent Valdez in his studio, 2016. © Michael Stravato “I hold very firm in my belief today that art and artists can still play a social role and that art can provide very crucial, critical moments of silence and reflection during moments of immense distortion and chaos.” - Vincent Valdez When the viewer confronts Valdez’s monumental painting, the eye first settles and lingers on the Klan members, infamous for their systematic and deadly targeting of mainly African American communities but also Latinos, Catholics, Jewish people, immigrants, and members of the LGBT community. Valdez discussed the disjunction between the beauty of their rendering and the horror of the Klan’s actions with journalist Maria Hinojosa of NPR’s “Latino USA” on the opening night at the Blanton Museum of Art. “Full blown raw reality is supposed to hit you. I lure you in with that beauty and I keep you there just enough so that you aren’t distracted within two seconds and back on your cell phone,” Valdez said. “If I can keep your attention, draw you in and keep you there, then that’s when the power of art really starts to unfold because you start to think critically.” Should attention shift to a cell phone, viewers will be met with a disconcerting reflection of themselves in the image of a Klansman who casually checks his phone. Close looking through the peaked hoods brings into high relief the significance of the gridded city in the background. Like the Klan members whose images encapsulate many forms of overt racism, the portrait of the city in the distance also assumes an allegorical role in the painting. City designs throughout the country play a key part in the systematic disenfranchisement of communities of color and immigrants. In discussing the point with Hinojosa, Valdez targeted a few of the many elements that are part of a whole system that disadvantages communities of color. County jails, high-density housing projects, and liquor stores are disproportionately placed in low income neighborhoods. Access to high-quality educational and health resources, on the other hand, are largely absent from the same communities. Underscoring the invisibility of some parts of the larger system of disenfranchisement, Valdez questioned, “Who gets trees and parks and playgrounds? Who gets access to these things?” His question conjures the image of the toddler whose pointing gesture seems to recruit the viewer to participate in a lifestyle that will ultimately support his ability to thrive. The Blanton Museum of Art also purchased the pendant piece, “The City II” (2016), which features a desolate dumping ground populated by abandoned mattresses, furniture, and television sets. “The City II” has received significantly less attention than its more jarring companion piece, yet, it is crucial in understanding a key theme that unites the multi-panel installation: American consumerism directly supports the maintenance of white supremacy. The iPhone, baby Nikes, special edition Budweiser beer can, and late model Chevrolet serve to locate the painting in the present. But these details set alongside the cast off possessions piled high in “The City II” also remind the viewer that the American drive to consume exacerbates and maintains vast racial and economic divides. “For far too long it’s been too easy for America to avoid the conversation about racism and how it is so embedded in our American DNA and our way of life,” Valdez said. Valdez began painting “The City” in 2015, during Barack Obama’s presidency. Now viewed in the context of the current administration, we might ask whether “The City” themes resonate more with today’s audience. By no means are individual or structural racism new to this nation. Nonetheless, discussions about white supremacy, structural racism, and xenophobia have reentered our conversations with alarming normalcy since the November 2016 election. If Valdez’s “The City” resonates more today in the midst of tweetstorms, inhumane immigrant child detainments, and continued killings of unarmed black men and women, it is because now, more than ever, we require critical moments of silence and reflection in times of political distortion and chaos. Vincent Valdez, The City I, 2015–16 (detail). Oil on canvas, 74 x 360 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of Guillermo C. Nicolas and James C. Foster in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, with additional support from Jeanne and Michael Klein and Ellen Susman in honor of Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2017. © Vincent Valdez. Photo by Peter Molick. Vincent Valdez’s “The City” can be seen at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin, through October 28, 2018. Andrea Lepage is associate professor of art history at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. As a scholar of Latino/a and Chicano/a visual culture coming out of the west, Lepage explores contemporary art as a form of social practice. Her many published writings include the essay “Reconstructing the Curriculum at El Taller Siqueiros, c. 1977: Judith Baca’s ‘Intensive Course in Mural Painting in Cuernavaca’ ” in “BACA: Art, Collaboration and Mural Making” (Angel City Press, 2017). |

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|