|

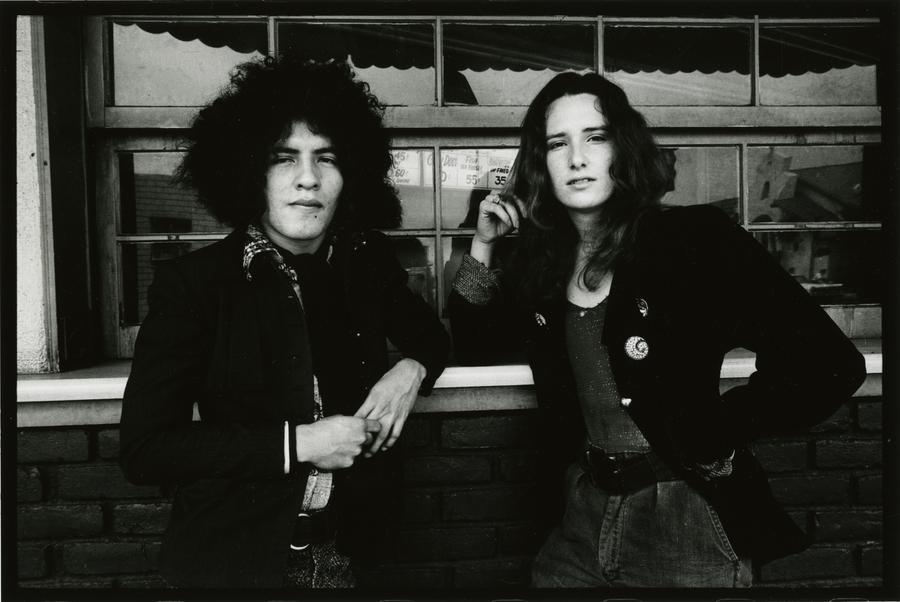

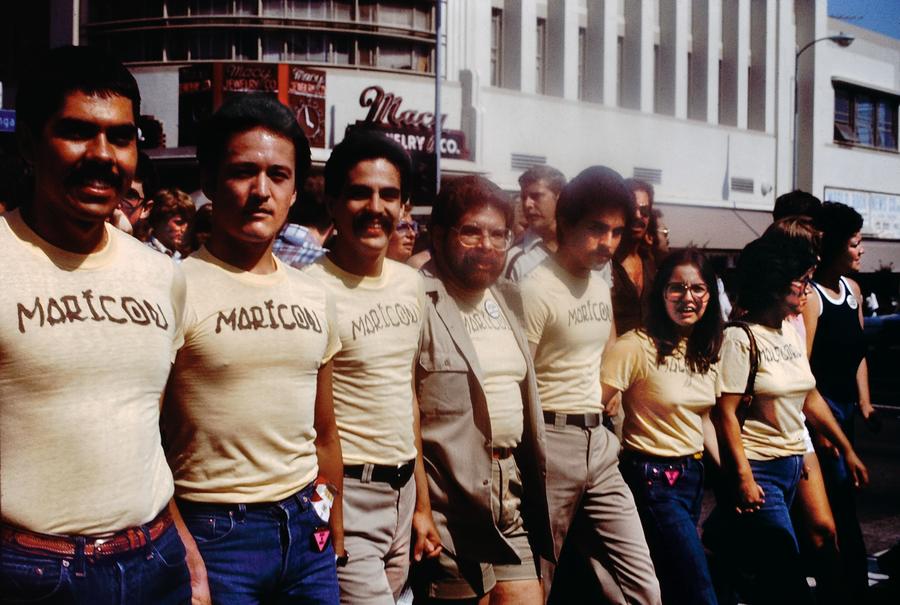

Anthony Friedkin, Jim and Mundo, Montebello, East Los Angeles, 1972. From The Gay Essay, 1969–73. Gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 in. Gift of Anthony Friedkin. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Courtesy of Anthony Friedkin This is art that speaks, screams, and whispers from behind the complex layered nature of being a queer Chicanx artist living and working in a Los Angeles of another time. Soon you will be able to mingle with 150 of those works from fifty artists created during an era when it was dangerous for them to be themselves. “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” is curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz and now on a U.S. tour will make a stop at the UNLV Barrick Museum of Art. Early research for “Axis Mundo” became an excavation of artworks showing how the beginning of the Chicano Movement had help beyond marching and protesting. More help came from a network of painters, photographers, and performers who found solidarity with each other and produced art laced with an early queer aesthetic that challenged the ideas of art and identity during the late 1960s and through the early '90s. Any Chicanx artist working solo outside mainstream cultural circles would not come close to making social change, much less anyone with sexuality badges. These artists tried to do it together. They were cued by the Chicano Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, jumped in to support Gay Activism during the 1970s, and then created art against a backdrop of AIDS awareness in the 1980s and 1990s. Now the works are tagged with scholarship that speaks to the radical use of genres, venues, and mediums. It is not just exploration of a lost art movement, or a sentimental homage that orbits around a central figure. “Axis Mundo” adds context to a regional avant-garde working within sub-cultures isolated from social and art institutions. Mundo does connect with a symbolic figurehead; a visible mascot for the creative free-for-all. It is the not-so-well-known artist Edmundo “Mundo” Meza, born in Tijuana in 1955, who died of complications due to AIDS in 1985. Meza migrated to the U.S. to be raised in East Los Angeles and was a painter turned performance artist, then played with the iconography and function of fashion, and used window displays for site-specific installations. He collaborated with other East L.A. artists by approaching art-making as a multidisciplinary practice. “Axis Mundo” is word-play on axis mundi, the cosmic connection between earth, heaven and hell. With “mundo” switching out “mundi” there is a linguistic transference from Latin to Spanglish. By using Meza as a namesake, curators Chavoya and Frantz use mundo as an eponym for the social solidarity between low and high-profile Chicanx artists. “It was amazing curatorship. I don’t know how they found the images,” says Judith Baca, whose work is featured in the exhibition. “There’s stuff that I haven’t been seen in years. They dug images up from the past.” Knowing the soul of “Axis Mundo” is understanding how the mash-up of styles and artists are still informing, or competing, with each other, grappling for identity while dodging established “-isms.” That is the virtuosity in this ephemeral mix of materials and lifestyle. Some works are as simple as mail cards printed to be distributed to those living in East L.A. proper, or t-shirts with street smart declarations, all made possible because low cost reproduction infiltrated graphic arts. Printed pieces become high concept messaging made possible by what is now considered lo-fi technology. That allowed ideas that bent expectations of identity, while calling out for civil rights or later speaking out against a government's apathy to the AIDS crisis, to be assembled with dexterity. The walls the artist faced were not just homophobia or closed doors of art institutions. Being Mexican-American often meant being raised Catholic, more of a cultural assignment than spirituality choice, and some works respond to the Brown Church. You can sense how a few makers of queer Chicanx art were conflicted as they sought to maintain artistic rebellion with personal faith. Back then, art by Mexican-Americans was often dismissed, unless it had folk art prompts or was painted on an inner-city wall. Those artists were not considered suitable candidates for art academia or able to engineer broad conceptual ideas. It was a different world then and there were other stigmas, recalls Baca, adding it was just dangerous to be queer. “The White male (artist) could be ‘out’ without impunity,” she says. You can see that when one considers artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, who was free to push themes. Yet, gifted painter Carlos Almaraz had his sexuality stored in a conditional state of being; being Gay was as underground as being Chicano. “The word 'Gay' is a White male invention. Oscar Wilde, to me, is its inventor,” says Gronk (born Glugio Nicandro), the painter, conceptual artist, and founding member of the art collective ASCO. He also has works in the exhibition. Gronk deems “Axis Mundo” is testament that the American avant-garde underground was not reserved for Whites Only. This was the West Coast edition of artists sharing the experience of visual experimentation, partying, locked in conflict and embrace, all while making art beyond painting, as practiced at Andy Warhol's The Factory. “It has painting for sure,” says Gronk. “But a lot of the work was concept based, like mail art, and graphics.” Instead of housed in a Manhattan loft, the centralized social state of the mundo-minded was East Los. Judith F. Baca, Documentation of Vanity Table, a performance for the exhibition Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer at the Woman’s Building, September 1976. Woman’s Building Records. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Judith F. Baca. “We were bending everything back then,” says Baca, who is featured in photographs that had her portray a confident Chola, staring back, or ignoring a camera lens, in 1970s document of Pachuca visual identity, where fashion, hair, eye make-up and attitude were codes for defiance. The series was her 1976 performance “Vanity Table” for “Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer” at the Woman’s Building, home of the influential Feminist Studio Workshop. The touting of “Axis Mundo” leans to being about landmark engagement by male and female queer artists within L.A’s Chicano culture using the spirit of Meza as a banner of alternative creativity. Still, while queerness is the true center of the exhibit, the scared site, the axis mundi; sexuality was not the focus or obsession of all the artists. “There are so many other words that describe sexual orientation,” says Gronk. “I don't use any and I really don't care what word is used. Call me ‘Artist’.” Fundamentally the networking a way to give each other support while each person explored how to dedicate an art affinity to be intimate with. “I thought of myself as a feminist, and muralist,” says Baca. “Social justice was my primary identify.” Thankfully, "Axis Mundo” pulls back on references to campy aesthetic. The exhibition is more than a display of artifacts with historic civil rights themes, or the memory of artists wanting to simply exist through their work. By taking the works on the road, from L.A. to Colorado, then New York, now Las Vegas, and soon Texas, curators Chavoya and Frantz clarify the long-standing legacy was the networking. By distributing information to like-minded masses and new eyes, "Axis Mundo” stands in for the 'zines and mail cards once sent to other artists producing visual experiences informed by queerness and ethnicity. That allows more passage across the borders of contemporary American art without apology, and (almost) without drama; to be transitional so others will consider producing works with the new dare and flair. It also states being a Chicanx queer thinker, which was a once a stigma, can be treated as a matter-of-art-fact. Or as Baca says, "Now it's 'Yes . . and?'" Participants in the Christopher Street West Pride parade wearing Joey Terrill’s malflora and maricón T-shirts, June 1976. Terrill appears third from the left. Photo by Teddy Sandoval. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas.

0 Comments

Cory McMahon Photo PaintThisDesert FIELD NOTES: Cory McMahon is a painter who carries a peaceful aura. Don’t be fooled. His experimental work is a fury of strategic risks. Coming in the UNLV MFA Studio Art program he was known for his large-scale abstraction. One time he has an earlier work, a large painting, on the back wall of then CAC gallery for a group show. It caught the eye of art critic Dave Hickey, who was sitting on his throne across the room waiting to chat up “25 Women: Essays on Their Art.” Hickey looked up from his cup of coffee, saw the large canvas with fierce brush strokes and, in that Southern one-part-warm two-part-grumble, asked whoever was listening: “Who the hell did that? . . . It’s good.”

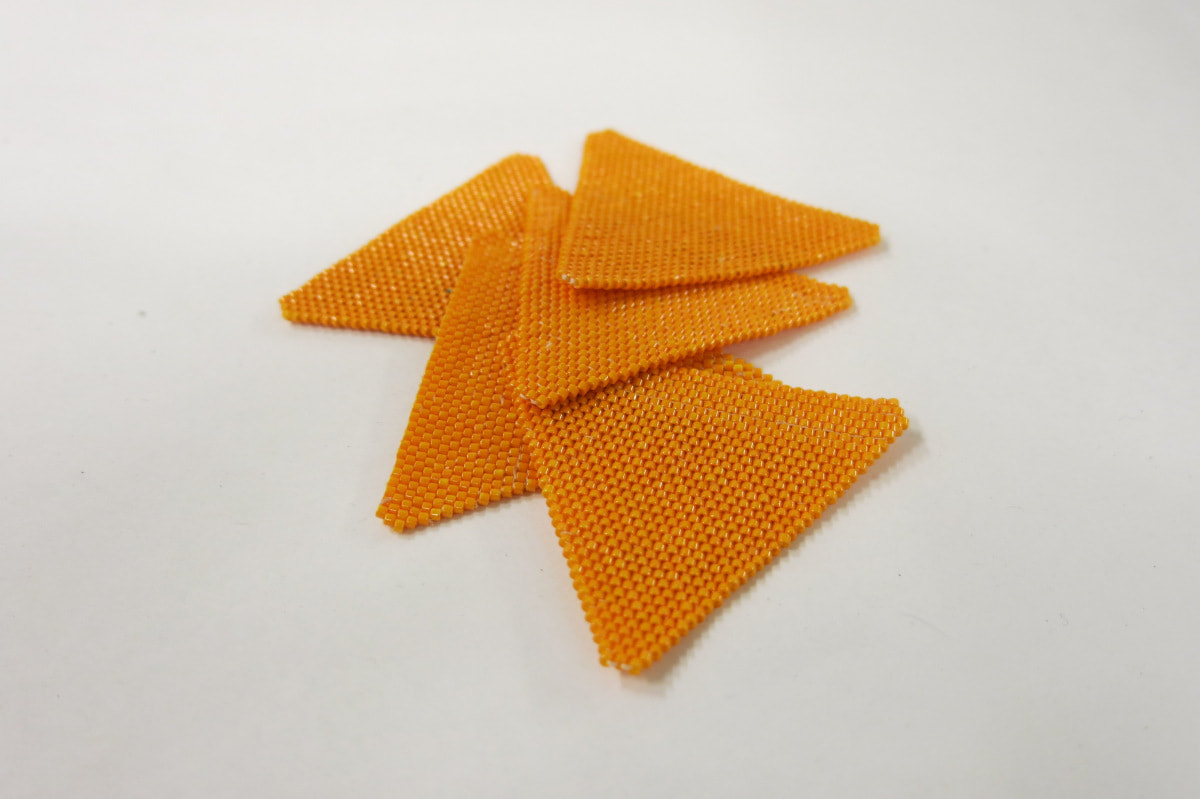

During his time at UNLV McMahon looked to go further. When the graduate students held an open house, he checked out hardbound dissertations from the UNLV library and stacked them in a display window. He called the installation ‘An Investigation of Analysis of. . .” McMahon even left his safe house of painting for his midway to explore ideas. That exhibition wasn’t what was expected. So, what? I thought. That’s the point, isn’t it? To take chances. McMahon's thesis show opens February 26. From his description, he is exploring the ideas of artist intent. I am looking forward to what he says about that through his art. The reception is March 9. Cory McMahon “Perfect Form” February 26 - March 10 Reception March 9, 2018 Noelle Garcia "Doritos" 2016 New exhibitions at the Barrick Museum of Art, and early rounds of MFA exhibitions at the Donna Beam and Grant Hall Gallery, will make the second Friday of February a busy evening. The Spring Exhibition season opens February 9, 2018, from 5 – 9 p.m. "The museum and gallery spaces of the UNLV campus invite you to examine ways in which different artists have explored the intersection of identity and form." Plural Plural features recently donated artworks from the UNLV Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art's permanent collection that explore complex aspects of human identity through a range of traditional and unconventional media. Memory, passion, voice, excess, race, gender, and intersectionality are all brought into question as we search for ways in which a museum collection can reflect our own multifaceted understanding of what we are. This exhibition features artwork by China Adams, Linda Alterwitz, Audrey Barcio, Tim Bavington, Elizabeth Blau, Catherine Borg, Diane Bush, Gig Depio, Andreana Donahue, Jacqueline Ehlis, Justin Favela, Ash Ferlito with Matt Taber, Noelle Garcia, Nancy Good, Maureen Halligan, Clarity Haynes, Stephen Hendee, Brent Holmes, Bobbie Ann Howell, Alexa Hoyer, Eri King, Branden Koch, Fay Ku, Wendy Kveck, Eric LoPresti, Julie Oppermann, Tom Pfannerstill, Krystal Ramirez, Kim Rugg, JK Russ, Sean Russell, Daniel Samaniego, Aaron Sheppard, Sean Slattery, Lance Smith, Brent Sommerhauser, Laurens Tan, Ryan Wallace, Mary Warner, Mikayla Whitmore, Thomas Ray Willis, Amy Yoes, and Almond Zigmund. Identity Tapestry Mary Corey March "Identity Tapestry" is both a portrait of a community and each individual participant. Inviting visitors to weave aspects of themselves into a participatory artwork, artist Mary Corey March gives us new insights into both ourselves and the people we see around us every day, opening our minds to reflection and healing. The 20-foot long installation, made of hand-dyed yarn, and statements of identity and lived experience that range from "I am a woman" to " I am fortunate" will join UNLV's permanent collection. This exhibition and accompanying programs are produced by the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art and Nevada Humanities, with support from the UNLV College of Fine Arts, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. VESSEL: Ceramics of Ancient West Mexico "Vessel" explores the relationship between form and function through ancient West Mexican ceramics. The exhibition is organized by shape, and visitors are invited to contemplate how the form of each vessel informs both practical use and communicates ideas of power, identity, and belief. Curated by UNLV alumni and Museum staff, Paige Bockman, M.A. Anthropology 2015. Brandon Lacow Brandon Lacow "on the fence" Thesis Exhibition Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery January 29 - February 9, 2018 Closing Reception: Friday February 9, 6 - 9 p.m. Holly Lay Midway Exhibition UNLV Grant Hall Gallery Closing Reception: Friday February 9, 6-9 p.m. |

An Online Arts Journal

Exhibition:

February 2 – March 31, 2019 Artist Reception and Gallery Talk: Sunday, February 10, 2019, 4 p.m.–7 p.m. S P O N S O R

ARCHIVES

January 2019

TAGS

All

|