|

Robert E. Lee monument Emancipation Park with handmade sign reads "Heather Heyer Park." Photo: Andrea Lepage Paint This Desert invites Andrea Lepage, associate professor of art history, to share her thoughts that come from witnessing the climate and mood of her region. With her scholarship in Chicanx Art, social practice, and art in public space, all while teaching below the Mason-Dixon Line, Lepage has intimate insight to recent events. While there will be much debate about the role of civic art as public art, it can be agreed that sculpture in public space around the U.S. will be watched and read more closely. By Andrea Lepage It has been a painful and violent week for Virginia, and for the nation. When racist hate groups—neo-Nazis, white nationalists, and Klansmen among them—descended upon Charlottesville, Virginia, they did so with the promise that they would defend not just the Robert E. Lee monument located in Emancipation Park, but also their perceived right to supremacy. By the end of the day on August 12, 2017, 32-year-old anti-hate activist Heather Heyer had been brutally murdered and 19 others injured when a white nationalist drove his vehicle into them. Two police officers had died in a helicopter accident. Deandre Harris had been brutally beaten. Dozens—maybe more—had been injured in violent clashes within opposing crowds that law enforcement officials were either unable or unwilling to keep apart. The driver, James Alex Fields, Jr., was charged with second-degree murder and other counts after authorities say he drove into the crowd. Other white supremacists came to Charlottesville heavily armed, ready to kill, and if we take them on their own word, prepared to continue the killing to achieve their Radical White Supremacist terrorist agenda. I write from the perspective of one Virginian (though a transplant) who, while disgusted, was not surprised by the violence enacted by white supremacists that day in Charlottesville. The fliers that I have seen announcing the “Unite the Right” action provided advance warning and included slogans such as “We will not be replaced,” “March with us on Charlottesville,” and “This Time we Fight Together.” Only occasionally were the Confederate monuments around which they marched invoked explicitly in the propaganda. One such example includes this proclamation: “This is not an Attack on Your Heritage, This Is an Attack on Your Racial Existence. Fight Back or Die. […] Stand for Our Monuments.” Members of the same organization that issued that recruitment poster were among those white supremacists who carried torches and chanted “You will not replace us” and “Jews will not replace us” as they marched through the University of Virginia campus on August 11. Their actions and words make clear that their nativist rhetoric serves the much larger purpose of oppressing people of color, Jews, Muslims, immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community, and women. Their actions also force us to consider the role of public art in our society. As so many other commentators have already pointed out, the conflict over Confederate monuments, memorials, and symbols long predates the “Unite the Right” action in Charlottesville. Still, it is worth exploring two recent events to see that we have been on the path to Charlottesville for quite some time. (I could take this discussion back to before the foundation of the United States of America, when Europeans committed genocide against the original inhabitants of the land, but I’ll only go back a couple of years here). Confederate flags flying on public land throughout the country have been under considerable scrutiny, though activist Bree Newsome’s removal of the Confederate flag flying outside the South Carolina statehouse received the most recent media attention. In an act of defiance against the state-sanctioned flying of the flag (first put into place during the early Civil Rights era), Newsome climbed the flagpole just days after Confederate-flag-waving white supremacist Dylann Roof viciously assassinated nine parishioners at the historically black Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, SC in June of 2015. In May of 2017, amidst much controversy, the city of New Orleans removed a series of public monuments to Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Robert E. Lee. Symbols of the Confederacy have grown so contentious that New Orleans municipal workers were clad in bullet-proof vests when they took down their Confederate memorials in the early morning hours of May 11, 2017. Protesters in the crowd yelled “There’s a lot more of us coming!” threatening an impending battle, and “The South will rise again,” with its inherent promise that after losing the Civil War, the South will win the next fight, presumably against the United States. In his speech, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu made clear his rationale for the removal of the monuments, saying, “These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.” Elsewhere in his speech, printed in its entirety in the New York Times, Landrieu likened Confederate monuments to another form of racialized terror—cross burning—noting that the memorials were strategically placed to intimidate and terrorize New Orleans’s black citizens. Southern Poverty Law Center, “150 Years of Confederate Iconography,” In Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy. Image source: www.splcenter.org The Southern Poverty Law Center’s 2016 report, “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy,” presents compelling research that backs Landrieu’s suggestion. In 2016, the SPLC counted at least 1,503 publicly-sponsored symbols of the Confederacy in public spaces and over 700 Confederate monuments and statues located on public property. The SPLC count includes “monuments and statues; flags; holidays and other observances; and the names of schools, highways, parks, bridges, counties, cities, lakes, dams, roads, military bases, and other public works.” Unsurprisingly, the majority of the symbols (1354 or 90%) are situated in the states that made up the former Confederate States of America, with Virginia (223), Georgia (174), North Carolina (140), Mississippi (131), and Texas (128) topping the list with the most memorials to the Confederacy. The vast majority of the public monuments surveyed by the SPLC were placed in their present locations during two specific historical periods: the first two decades of the twentieth century during Jim Crow and during the Civil Rights movement. Such is the case with the Charlottesville monument around which the Ku Klux Klan marched in July 2017, and which again drew the attention of the so-called “Alt-Right” a month later. One hundred years earlier, in 1917, Charlottesville resident Paul Goodloe McIntire commissioned Henry Shrady to execute the sculpture as part of a nationwide City Beautiful movement (1919-1924). Charles Mulford Robinson’s The Improvement of Cities and Towns (1901) provided a practical manual to guide the beautification of U.S. towns and cities. He had this to say about “The Function and Placing of Sculptures”:

Given the context of its creation, it does seem that the Charlottesville monument was meant to be educational, though not in morally upright ways. It is worth mentioning here that 1917, the date of the sculpture’s commission, was two years after the release of D.W. Griffith’s enormously popular film, The Birth of a Nation, which depicted the Ku Klux Klan as honorable defenders of southern values. Many have credited the film, which received the highest praise from then-president Woodrow Wilson, with the reemergence of the Klan (originally founded in 1866, but disbanded shortly thereafter). As the SPLC survey indicates, the nation saw a spike in Confederate monument building at that time, though the pace of construction was significantly slower than it had been at its height in 1910–11. When the sculptor Shrady died, the commission was passed on to Italian artist Leo Lentelli, who had immigrated to the U.S. in 1903. Upon completion, a crowd celebrated the installation of the Shrady/Lentelli equestrian statue in 1924. According to writer Jamelle Bouie, the statue was presented in conjunction with a Confederate reunion celebration. Participants included Confederate veterans, Sons of Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and one hundred cadets from the Virginia Military Institute, who Bouie notes were decorated in Confederate colors for the occasion. Writer Eileen Johnson contends that some of the members of the crowd wore white hoods to the ceremony. Klan membership at the time in the area is well-documented, and religious studies scholar Jalane Schmidt has shown how—much like in other southern towns—the Charlottesville Klan boasted clear institutional support. In her essay, “Excuse me, America, your house is on fire: Lessons from Charlottesville on the KKK and 'alt-right' ”, Schmidt references a story in the February 10, 1922 edition of the Charlottesville Daily Progress that indicates that the county sheriff was a member of the KKK. By 1927, the Klan boasted more than four million members, a number that reminds us that white supremacist ideology was not located on the fringes of society, but rather was well accepted in the mainstream.

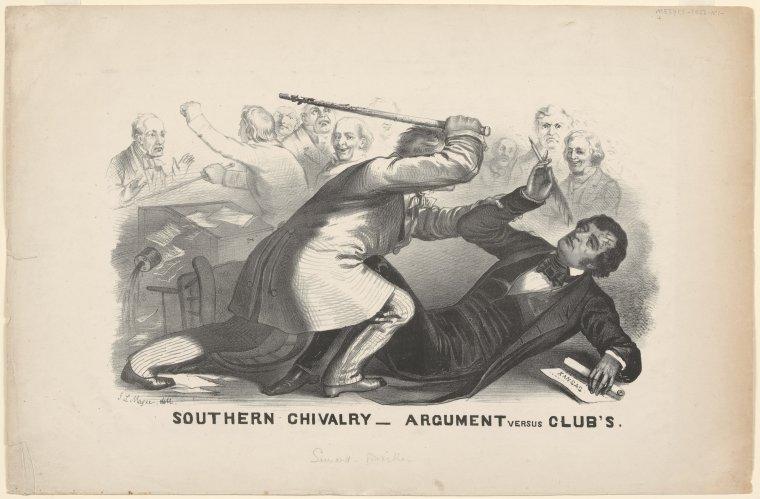

In the monument, Lee is shown in uniform, with his sword ready at his side. Unlike the historical Lee, who surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865, this sculptural surrogate has not yet put down his battle sword and rides upon his horse Traveller in perpetual resistance to the dismantling of the institution of slavery for which he fought. The sculpture embodies the ideas of slavery, which include the white supremacist ideologies that made it acceptable for whites to kidnap, buy and sell, enslave, brutally beat, and viciously rape black men and women. As Mayor Landrieu noted, these statues, located on public land, are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. On public land, and absent anything but a celebratory context, these monuments embody antiquated ideas that no longer reflect our societal values. A common argument, forwarded on social media and white supremacist websites is that the removal of Confederate monuments, memorials, and symbols from public land is tantamount to erasing Confederate leaders from history altogether. History, of course, cannot be erased. Certain events, however, can be ignored, suppressed, disregarded, or purposefully discarded. Some tellings of history might, for example, promote Lee as a complex but honorable man of his time and ignore or disregard his role as the leader of the army that fought to maintain the enslavement of people. It is worth noting here that the “Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials, and Public Spaces” assembled by the Charlottesville City Council to study the placement of the city’s Confederate monuments made this explicit recommendation regarding the Confederate monuments: “This commission suggests that the Lee and Jackson statues belong in no public space unless their history as symbols of white supremacy is revealed and their respective parks transformed in ways that promote freedom and equity in our community.” In 2015, an activist anticipated such recommendations and placed Lee into a larger context by scrawling the words “Black Lives Matter” across Blair’s granite base. The words were quickly removed, though a faint trace remains visible. To test out the belief that the public may be in danger of forgetting about Confederate history if we remove the Charlottesville monuments from public view, I turned to a Virginia state public high school history textbook. As it turns out, Virginia’s current version of a United States History (Prentice Hall, 2011) textbook has a great deal to say about the Civil War and Confederate history. It is an important chapter in Virginia’s official narrative delivered to each public-school student. If we include the events leading up to the Civil War as well as Reconstruction, the Virginia state textbook actually contains three chapters (of thirty-three) focused on the period between 1846 and 1877. In the one hundred pages that make up this section, Robert E. Lee is referenced on nine separate pages, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson is mentioned on four different pages. Despite right-wing white supremacist appropriation of narratives of erasure, even a cursory glance at state-sanctioned history makes it clear that Virginia’s youth are in no danger of forgetting about the Confederates of the past. On the contrary, they are steeped in material that privileges the Lost Cause revisionist version of events listed under headings such as “Slavery, States’ Rights, and Western Expansion,” “A Rising Tide of Protest and Violence,” and “The Klan Strikes Back.” Magee, John L., “Lithograph of Preston Brooks' 1856 attack on Sumner,” Digital Public Library of America, Courtesy of Kansas City Public Library via Missouri Hub. The tone, which purports to provide an unbiased version of history, is at times alarmingly absent of a moral compass to guide students, who might never go on to study U.S. history at a collegiate level. I have selected one example as a case in point, due to its odd resonance with the recent white supremacist violence in Charlottesville. The passage refers to Charles Sumner, who delivered “The Crime Against Kansas” speech to the Senate in 1856, in which he argued for Kansas to be admitted to the Union as a free state and denounced slavery as a depraved institution. His speech and his indictment of slavery were not well-received by some southern senators. On the topic, the Virginia textbook reads:

The textbook fails to fill in the content of Sumner’s “insult.” In fact, Sumner characterized Butler as a dishonorable man for being in bed with the institution of slavery, saying: “Of course [Butler] has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, slavery.” A casual reader of the Virginia textbook version of this episode might think Sumner had a beating coming; the textbook implies as much. Another reader might walk away with the notion that a verbal insult, if we can call it that, justifies a nearly deadly beating. Nowhere in this story is there a suggestion that some people, Butler and his family for instance, were so deeply invested in the institution of slavery that they were willing to do violence to preserve it. If the Charlottesville monuments come down, the ideas that bred the violence in Charlottesville remain in place, deeply embedded within the structures of our educational system, its curriculum, and even in the naming of our schools. The SPLC has counted 109 public schools named after Confederate generals, many with large populations of African American students. Citizens and visitors across the nation are reminded of their presence each day as they walk through the streets that bear the names of Confederate commanders. Charlottesville’s monument to R.E. Lee still stands in a public park, despite the fact that the city’s elected officials voted for its removal after measured consideration. But, in the few short days since the “Unite the Right,” action, Confederate monuments have come down in other cities throughout the country. Protesters toppled a Confederate Soldiers monument in Durham, NC on August 14. In the early morning hours of August 16, the city of Baltimore quietly took down the Lee and Jackson monument, the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors monument, the Confederate Women’s monument, and the Roger B. Taney monument. Taney was the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court who delivered the majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which among other things, denied black men and women the right to U.S. citizenship, to exercise legal rights, and prohibited the U.S. government from freeing enslaved people in the territories. It would take a magical feat of whitewashing to cast that monument as anything but a memorial to white supremacist ideology. The removal of Confederate monuments from public property in other cities will follow, as the dismantling process unfolds. While public monuments and memorials sit symbolically at the center of this clash, it is the white supremacist ideas that they embody that are slowly being replaced. Photo: Andrea Lepage For more information about Charlottesville’s deep history of white supremacy, racial discrimination, and racialized terror, read through “The Charlottesville Syllabus,” which contains a list of critical sources curated by the Graduate Student Coalition for Liberation. Editor Note: Previous Paint This Desert post by Andrea Lapage / "Vincent Valdez's 'The City' " (10.1.16)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

ABOVE: Justin Favela's "Gypsy Rose Piñata." at Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles.

Photo courtesy Petersen Automotive Museum ARCHIVES

August 2017

TAGS

All

|